Math Amateur said:

Hi fresh_42 ...

Thanks for the answer to Question 2 ...

I received the following answer to question 1 from Euge on the MHB Forum:

Since maximal right ideals of ##R## don't contain ##1## by definition, then ##J(R)##, the intersection of all maximal right deals, cannot contain ##1##. That's why ##J(R) \neq R##.

That's what I said.

But a maximal ideal isn't the entire ring anyways, isn't it? Simply by definition? It wouldn't make any sense to speak of maximal ideals being the ring itself. Of course ##R \trianglelefteq R## is always an ideal, so the concept of maximal ideals would be useless, if we allowed them to be the ring. In that case the maximal ideals were

always simply ##R##. That's why I didn't understand the bypass with ##1##. I simply don't see the necessity. The intersection of all maximal ideals, ##J(R)##, can only be smaller or equal than any maximal ideal. How could it become the entire ring?

Regarding the conditions ##J(R) = R## and ##J(R) = 0## ... ... ... ... I am still a little confused ...

Sorry, I wasn't clear on this one.

Let's assume a ring without any maximal ideals. Oops, this cannot be true, since ##\{0\}## is always an ideal. So at least ##\{0\}## would be a maximal ideal. In this case ##J(R)=\{0\}##.

Now I tried to understand the condition ##J(R)=R## somehow. I still think it is trivially always false. But let's see, what Blade might have thought. He makes the

convention ##Rad(M)=M \Longleftrightarrow R \text{ has no maximal submodules }## for modules and says something about an analogous case to ideals. Therefore I tried to interpret ##J(R)=R## by the same convention and assumed - as being analog - it might mean: no maximal ideals. But as shown above, this would imply ##J(R)=\{0\}## and both together ##R=J(R)=\{0\}##, which again is meaningless. Therefore, my thought, even with his convention for modules, the condition ##J(R)=R## doesn't make any sense. E.g. in my book, maximal ideals ##I## are defined as those, which are not ##(1)## plus there is

no ideal ##J## properly in between ##I \subsetneq J \subsetneq (1)\, .##

At least I don't see any flaws in my argumentation. Maybe I've overlooked some strange cases, but I don't see it. The argument with ##1 \in R## is only a shortcut for the thoughts above. Since we have a ##1##, we don't have do think about crude cases.

Personally I don't understand this convention, since with the same arguments as with ideals, ##Rad(M)## should be zero, if there are no maximal modules, because ##\{0\}## is always a submodule. I assume that Blade's definition of "maximal" - ideal or submodule - might exclude both cases ##\{0\}## and ##M## explicitly. Then he can make this conventions to have the notation ##Rad(M)=\{0\}## available for the cases where there are proper maximal submodules that intersect to zero, i.e. the case where actually something happens.

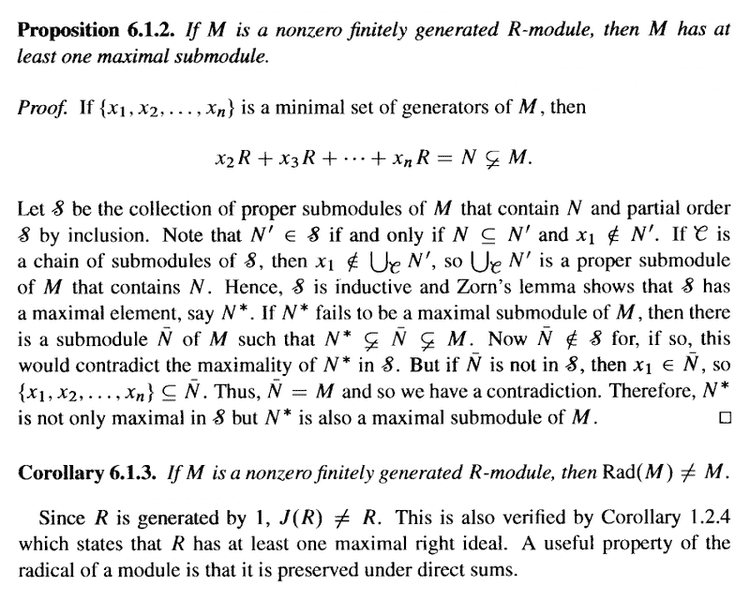

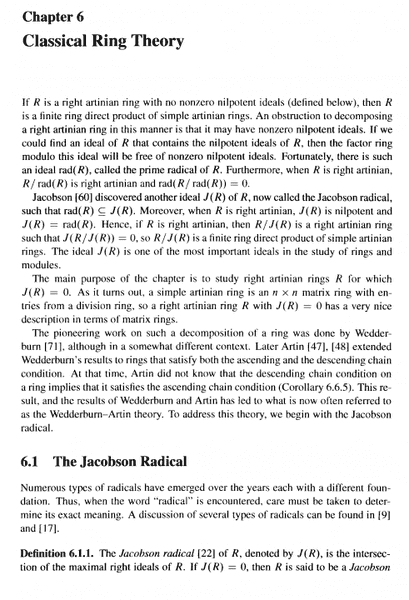

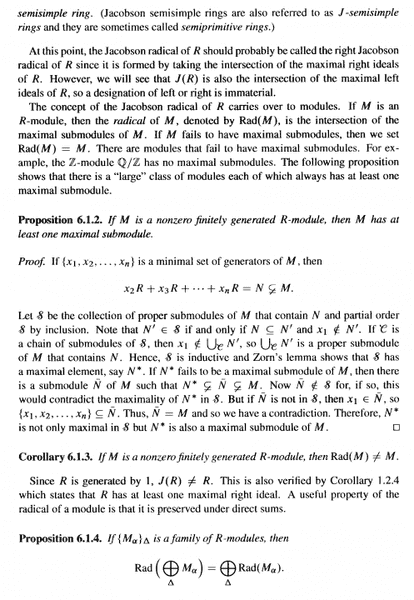

Regarding ##\text{ Rad}(M)## ... Bland is clear when it comes to ##\text{ Rad}(M) = M## ... indeed Bland's definition of ##\text{ Rad}(M)## is as follows:

"... ... If ##M## is an ##R##-module, then the radical of ##M##, denoted by ##\text{ Rad}(M)##, is the intersection of the maximal submodules of ##M##. If ##M## fails to have maximal submodules, then we set ##\text{ Rad}(M) = M##. ... ...

"Presumably ##\text{ Rad}(M) = \{ 0 \}## when there exist maximal submodules in ##M##, but their intersection is ##\{ 0 \}##Now, with ##J(R)## Bland does not explicitly give a condition for which ##J(R) = R## ... indeed his definition of the Jacobson radical is as follows:

"... ... The Jacobson radical of ##R##, denoted ##J(R)##, is the intersection of maximal right ideals of ##R##. If ##J(R) = 0##, then ##R## is said to be a Jacobson semisimple ring ... ..."

Yes, no objections.

Is it correct to assume that if there are no maximal right ideals in ##R##, then ##J(R) = R## ... ... ?

... ... and ##J(R) = 0## if there do exist maximum right ideals but their intersection is ##\{ 0 \}## ... ... ?

According to his convention with modules, and given a total analogy, it is correct, yes. I wouldn't make it for the reasons I mentioned above, but if he does, then it is correct.

Let's see what an important theorem says to the case. The theorem goes as follows:

$$ x \in J(R) \Longleftrightarrow 1-xy \in R \text{ is a unit for all }y \in R$$

Now if ##J(R)=R## then all elements ##1-xy## are units for all ##x,y \in R##. If ##I \subsetneq R## is a maximal ideal, then there is an element ##x \notin I## and ##xR+I=R##. So we can write ##R \ni 1=xy+z## for some ##z \in I##. Thus ##I \ni z=1-xy## is a unit by our assumption ##J(R)=R## and the theorem. But an ideal that contains a unit is the entire ring. Therefore our assumption that ##I## is a maximal ideal cannot be true and ##R## doesn't have any maximal ideals (other than ##\{0\}\,##).

So it seems to make sense to make this convention (##J(R)=R \longleftrightarrow \text{ no maximal ideals }##), which tells me that either I haven't seen it before, since most authors don't deal very much on these extreme cases, or I have forgotten it. As long as we are sure, what is meant by this, we can make this convention. Personally I think it's a source of possible errors and one has to be careful by deductions from ##J(R)=R## other than "

no maximal ideal, resp.

only ##\{0\}##

as maximal ideal", but o.k.

Let me renew an advice here. It's o.k. to spend some time thinking about those special cases and it certainly helps the general understanding, but don't forget to keep the basic ideas behind the definitions and propositions on focus.