Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

- TL;DR

- I need help in order to investigate two apparently different definitions of a local basis in a topological space ...

Fred H. Croom (Principles of Topology) and Tej Bahadur Singh (Elements of Topology) define local basis (apparently) slightly differently ...

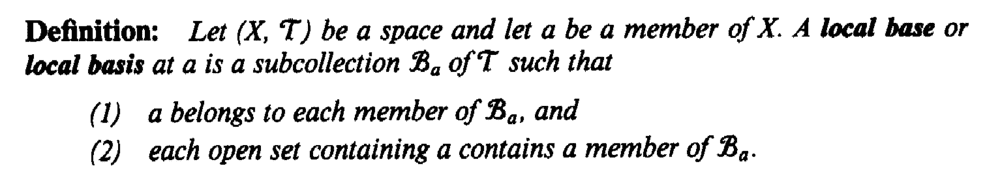

Croom's definition reads as follows:

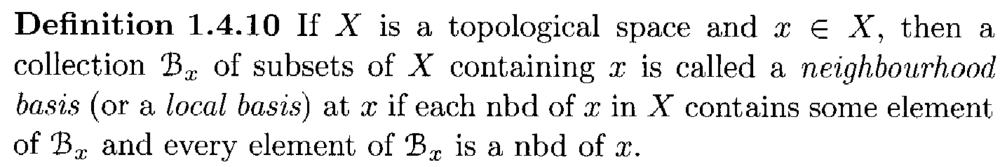

... and Singh's definition reads as follows:

... and Singh's definition reads as follows:

The two definitions appear different ... ...

Croom requires that each open set containing a contains a member of ##\mathcal{B}_a## ...

... while Singh requires each nbd of x to contain some element of a member of ##\mathcal{B}_x## ... and one notes that the open set (necessarily) contained in the nbd would necessarily intersect with a member of ##\mathcal{B}_x## ... it would not necessarily contain the member of ##\mathcal{B}_x## ... so I see the definitions as different ...

Is that correct?

If the definitions are indeed different ... which is the more common definition ...?

Further ... are their significant implications for further theory built on these definitions ...?Help will be much appreciated ... ...

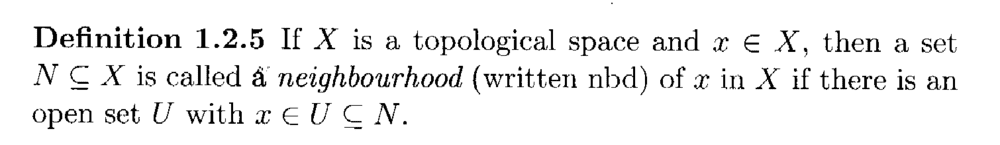

Peter=======================================================================================It may help Physics Forums readers of the above post to have access to Singh's definitions of a neighborhood (nbd) ...

... so I am providing the same ... as follows:

Hope that helps ...

Hope that helps ...

Peter

Croom's definition reads as follows:

The two definitions appear different ... ...

Croom requires that each open set containing a contains a member of ##\mathcal{B}_a## ...

... while Singh requires each nbd of x to contain some element of a member of ##\mathcal{B}_x## ... and one notes that the open set (necessarily) contained in the nbd would necessarily intersect with a member of ##\mathcal{B}_x## ... it would not necessarily contain the member of ##\mathcal{B}_x## ... so I see the definitions as different ...

Is that correct?

If the definitions are indeed different ... which is the more common definition ...?

Further ... are their significant implications for further theory built on these definitions ...?Help will be much appreciated ... ...

Peter=======================================================================================It may help Physics Forums readers of the above post to have access to Singh's definitions of a neighborhood (nbd) ...

... so I am providing the same ... as follows:

Peter

Last edited: