Aleoa

- 128

- 5

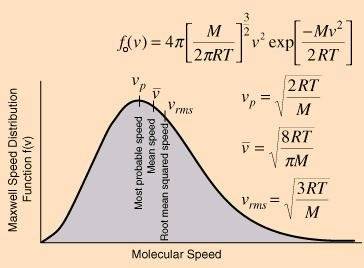

In the first volume of his lectures (cap 6-4) Feynman presents Maxwell's distribution of velocities of the molecules in a gas.

And, referring to the PDF graph he says:

And, referring to the PDF graph he says:

"If we consider the molecules in a typical container (with a volume of, say, one

liter), then there are a very large number N of molecules present (N ≈ 10^{22}).

Since p(v) ∆v is the probability that one molecule will have its velocity in ∆v,

by our definition of probability we mean that the expected number <∆N> to be

found with a velocity in the interval ∆v is given by: <\Delta N>=Np(v)\Delta v.

[...]

Since with a gas we are usually dealing with large numbers of molecules,

we expect the deviations from the expected numbers to be small (like 1/√N), so

we often neglect to say the “expected” number"

I have not understand this part, how it's possible to derive this 1/√N deviation ( or a value the gives the idea of what Feynman is saying) ?

Thanks for your support

"If we consider the molecules in a typical container (with a volume of, say, one

liter), then there are a very large number N of molecules present (N ≈ 10^{22}).

Since p(v) ∆v is the probability that one molecule will have its velocity in ∆v,

by our definition of probability we mean that the expected number <∆N> to be

found with a velocity in the interval ∆v is given by: <\Delta N>=Np(v)\Delta v.

[...]

Since with a gas we are usually dealing with large numbers of molecules,

we expect the deviations from the expected numbers to be small (like 1/√N), so

we often neglect to say the “expected” number"

I have not understand this part, how it's possible to derive this 1/√N deviation ( or a value the gives the idea of what Feynman is saying) ?

Thanks for your support