Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

- TL;DR

- I need help with Tom Lindstrom's proof that if f and g are measurable then so is f + g ...

I am reading Tom L. Lindstrom's book: Spaces: An Introduction to Real Analysis ... and I am focused on Chapter 7: Measure and Integration ...

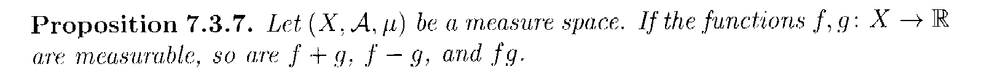

I need help with the proof of Proposition 7.3.7 ...

Proposition 7.3.7 and its proof read as follows:

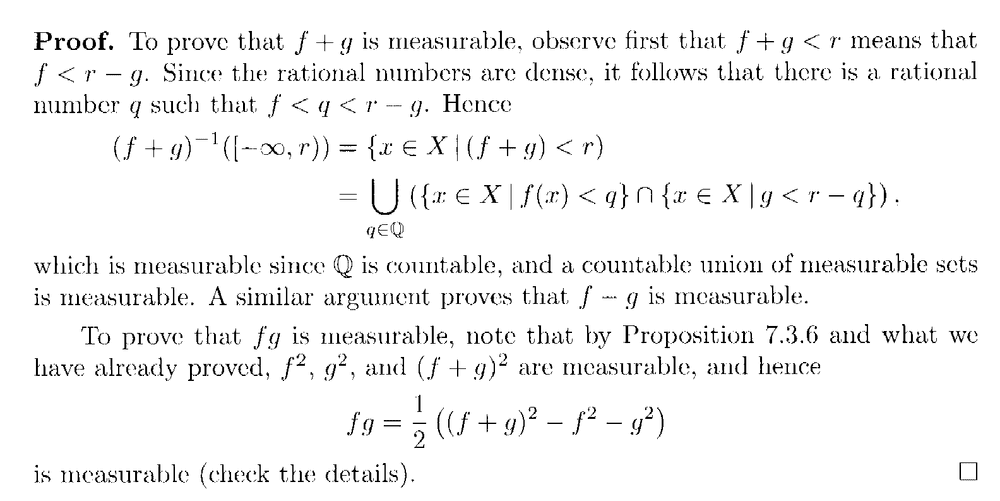

In the above proof by Lindstrom we read the following:

In the above proof by Lindstrom we read the following:

" ... ... ##(f + g)^{ -1} ( [ - \infty , r ) ) = \{ x \in X | (f + g) \lt r \}##

## = \bigcup_{ q \in \mathbb{Q} } ( \{ x \in X | f(x) \lt q \} \cap \{ x \in X | g \lt r - q \} ) ## ... ... "Can someone please demonstrate, formally and rigorously, how/why ...

##\{ x \in X | (f + g) \lt r \} = \bigcup_{ q \in \mathbb{Q} } ( \{ x \in X | f(x) \lt q \} \cap \{ x \in X | g \lt r - q \} )## ... ...

Help will be much appreciated ...

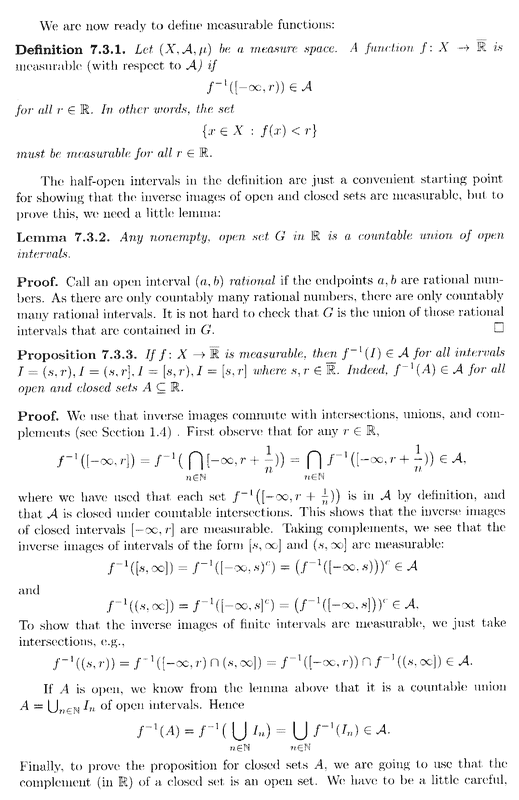

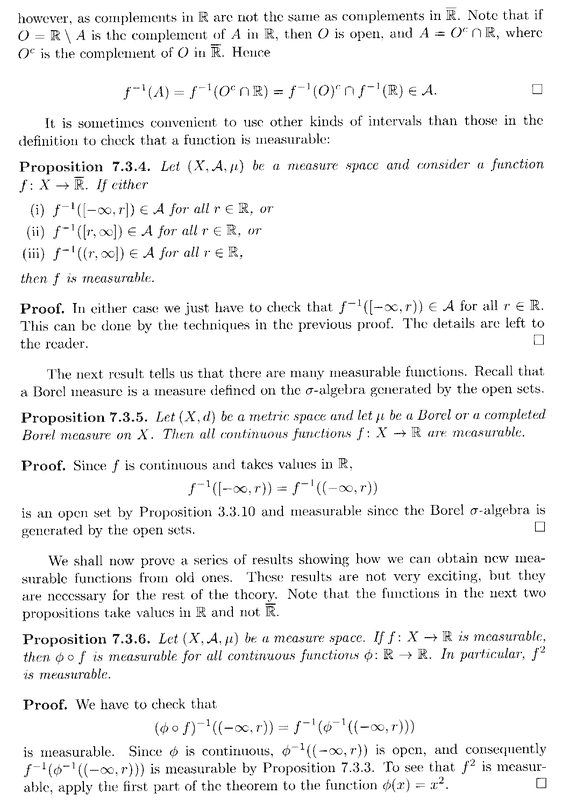

Peter=============================================================================================================Readers of the above post may be assisted by access to Lindstrom's introduction to measurable functions (especially Lindstrom's definition of a measurable function, Definition 7.3.1) ... so I am providing access to the relevant text ... as follows:

Hope that helps ...

Peter

I need help with the proof of Proposition 7.3.7 ...

Proposition 7.3.7 and its proof read as follows:

" ... ... ##(f + g)^{ -1} ( [ - \infty , r ) ) = \{ x \in X | (f + g) \lt r \}##

## = \bigcup_{ q \in \mathbb{Q} } ( \{ x \in X | f(x) \lt q \} \cap \{ x \in X | g \lt r - q \} ) ## ... ... "Can someone please demonstrate, formally and rigorously, how/why ...

##\{ x \in X | (f + g) \lt r \} = \bigcup_{ q \in \mathbb{Q} } ( \{ x \in X | f(x) \lt q \} \cap \{ x \in X | g \lt r - q \} )## ... ...

Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter=============================================================================================================Readers of the above post may be assisted by access to Lindstrom's introduction to measurable functions (especially Lindstrom's definition of a measurable function, Definition 7.3.1) ... so I am providing access to the relevant text ... as follows:

Hope that helps ...

Peter

Last edited: