vibha_ganji

- 19

- 6

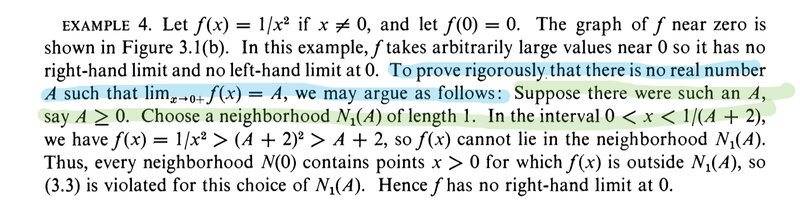

In Apostol’s Calculus (Pg. 130) they are proving that 1/(x^2) does not have a limit at 0. In the proof, I am unable to understand how they conclude from the fact that the value of f(x) when 0 < x < 1/(A+2) is greater than (A+2)^2 which is greater than A+2 that every neighborhood N(0) contains points

x > 0 for which f(x) is outside N1(A). I don’t get how they generalized the specific statement to all neighborhood of N(0). Thank you!

x > 0 for which f(x) is outside N1(A). I don’t get how they generalized the specific statement to all neighborhood of N(0). Thank you!