schniefen

- 177

- 4

- TL;DR

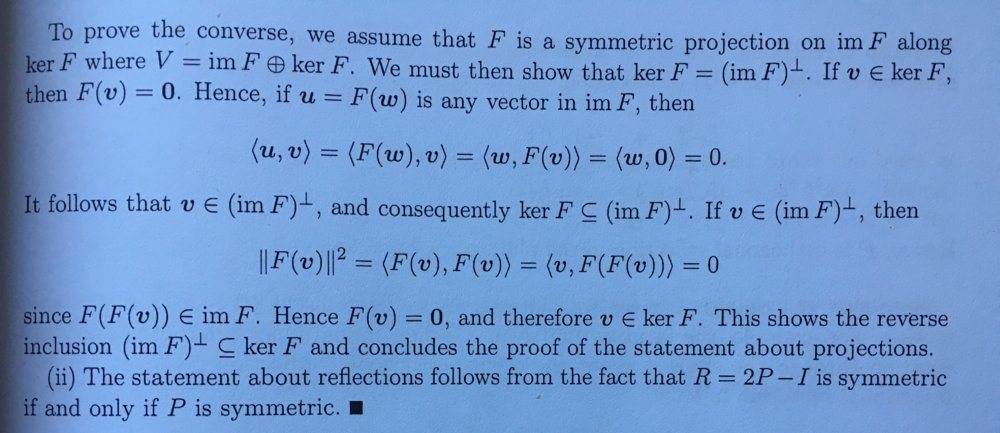

- This is a proof of a linear transformation ##F## on an inner product space ##V## being an orthogonal projection if and only if ##F## is a projection and symmetric.

The given definition of a linear transformation ##F## being symmetric on an inner product space ##V## is

In the attached image, second equation, how is the second equality justified? That is, ##\langle F(\textbf{v}), F(\textbf{v}) \rangle = \langle \textbf{v}, F(F(\textbf{v})) \rangle##. For projections in general, ##F=F^2##, but why does ##F(\textbf{v})=\textbf{v}## for ##\textbf{v} \in (\text{im} \ F)^{\perp}##

##\langle F(\textbf{u}), \textbf{v} \rangle = \langle \textbf{u}, F(\textbf{v}) \rangle## where ##\textbf{u},\textbf{v}\in V##.

In the attached image, second equation, how is the second equality justified? That is, ##\langle F(\textbf{v}), F(\textbf{v}) \rangle = \langle \textbf{v}, F(F(\textbf{v})) \rangle##. For projections in general, ##F=F^2##, but why does ##F(\textbf{v})=\textbf{v}## for ##\textbf{v} \in (\text{im} \ F)^{\perp}##