Sum Guy

- 21

- 1

Laplacian for polars:

$$\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left( r\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial r}\right) + \frac{1}{r^{2}}\frac{\partial^{2} \phi}{\partial \theta^{2}} = 0$$

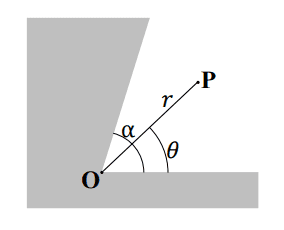

This is in relation to a problem relating to a potential determined by the presence of a wedge shaped metallic conductor (see image).

Working through the problem:

$$\phi (r,\theta) = R(r)\psi (\theta )$$ with $$R(r) \propto r^{v}$$ and Dirichlet boundary conditions $$\phi (r,0) = \phi (r,\alpha ) = V_{0}$$

Substituting into the Laplacian:

$$\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left( rvr^{v-1}\psi (\theta)\right) + \frac{1}{r^2}r^{v}\psi^{''}(\theta )$$

$$ = r^{v-2}\left( \psi^{''}(\theta ) + v^{2}\psi (\theta )\right) = 0$$

Therefore

$$\psi^{''}(\theta ) + v^{2}\psi (\theta ) = 0$$

Solution is of the form

$$\psi (\theta) = Acos(v\theta ) + Bsin(v\theta )$$

Applying BCs:

$$\phi (r,\theta ) = r^{v}\left(Acos(v\theta ) + Bsin(v\theta )\right)$$

$$\phi (r,0) = V_0 \rightarrow A = V_{0}r^{-v}$$

$$\phi (r,\alpha) = V_0 \rightarrow B = \frac{V_{0}r^{-v}(1-cos(v\alpha ))}{sin(v\alpha )}$$ ...which leaves me with utter crap.

However if we choose V0 such that it is zero then we can reapply the BCs:

$$\phi (r,0) = V_0 \rightarrow A = 0$$

$$\phi (r,\alpha) = V_0 \rightarrow sin(v\alpha ) = 0 \rightarrow v = \frac{n\pi }{\alpha}$$

Resulting in a more pleasant $$\phi(r,\theta ) = Br^{\frac{n\pi }{\alpha}}sin(\frac{n\pi }{\alpha}\theta )$$

So there a few things here that I'm struggling to understand:

If I don't set V0 = 0 then how can I solve the problem?

I should have a unique solution, yet B isn't determined?

How might I correct my solution so that the potential was V0 on the boundaries?

$$\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left( r\frac{\partial \phi}{\partial r}\right) + \frac{1}{r^{2}}\frac{\partial^{2} \phi}{\partial \theta^{2}} = 0$$

This is in relation to a problem relating to a potential determined by the presence of a wedge shaped metallic conductor (see image).

Working through the problem:

$$\phi (r,\theta) = R(r)\psi (\theta )$$ with $$R(r) \propto r^{v}$$ and Dirichlet boundary conditions $$\phi (r,0) = \phi (r,\alpha ) = V_{0}$$

Substituting into the Laplacian:

$$\frac{1}{r}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\left( rvr^{v-1}\psi (\theta)\right) + \frac{1}{r^2}r^{v}\psi^{''}(\theta )$$

$$ = r^{v-2}\left( \psi^{''}(\theta ) + v^{2}\psi (\theta )\right) = 0$$

Therefore

$$\psi^{''}(\theta ) + v^{2}\psi (\theta ) = 0$$

Solution is of the form

$$\psi (\theta) = Acos(v\theta ) + Bsin(v\theta )$$

Applying BCs:

$$\phi (r,\theta ) = r^{v}\left(Acos(v\theta ) + Bsin(v\theta )\right)$$

$$\phi (r,0) = V_0 \rightarrow A = V_{0}r^{-v}$$

$$\phi (r,\alpha) = V_0 \rightarrow B = \frac{V_{0}r^{-v}(1-cos(v\alpha ))}{sin(v\alpha )}$$ ...which leaves me with utter crap.

However if we choose V0 such that it is zero then we can reapply the BCs:

$$\phi (r,0) = V_0 \rightarrow A = 0$$

$$\phi (r,\alpha) = V_0 \rightarrow sin(v\alpha ) = 0 \rightarrow v = \frac{n\pi }{\alpha}$$

Resulting in a more pleasant $$\phi(r,\theta ) = Br^{\frac{n\pi }{\alpha}}sin(\frac{n\pi }{\alpha}\theta )$$

So there a few things here that I'm struggling to understand:

If I don't set V0 = 0 then how can I solve the problem?

I should have a unique solution, yet B isn't determined?

How might I correct my solution so that the potential was V0 on the boundaries?