Discussion Overview

The discussion revolves around a problem related to norm spaces, specifically focusing on the 1-norm and its properties. Participants seek advice on how to approach the proof and request resources for better understanding, particularly regarding the continuity of functions defined on normed spaces.

Discussion Character

- Exploratory

- Technical explanation

- Homework-related

- Mathematical reasoning

Main Points Raised

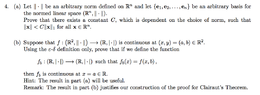

- Sam seeks advice on approaching a problem involving the 1-norm and requests resources for further understanding.

- Opalg clarifies the definition of the 1-norm and discusses the implications of using different bases for vector representation.

- Sam expresses confusion about the validity of a specific equality involving the norm and linear combinations of basis vectors.

- Opalg explains that every vector can be expressed as a linear combination of basis vectors and discusses the application of the triangle inequality in this context.

- Another participant provides a structured approach to proving continuity in part (b) of the problem, utilizing results from part (a) and defining a relationship between delta and epsilon.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants generally agree on the definitions and properties of the 1-norm and the approach to proving continuity, but there is no consensus on the overall solution to the problem as it remains under discussion.

Contextual Notes

There are unresolved aspects regarding the specific definitions of the norms and bases being used, as well as the continuity proof's dependence on earlier results.