fatpotato

- Homework Statement

- Find the max/min/saddle points of ##f(x,y) = x^4 - y^4## subject to the constraint ##g(x,y) = x^2-2y^2 -1 =0##

Use Lagrange multipliers method

Classify the stationnary points (max/min/saddle) using the definiteness of the Hessian

- Relevant Equations

- Positive/Negative definite matrix

Hello,

I am using the Lagrange multipliers method to find the extremums of ##f(x,y)## subjected to the constraint ##g(x,y)##, an ellipse.

So far, I have successfully identified several triplets ##(x^∗,y^∗,λ^∗)## such that each triplet is a stationary point for the Lagrangian: ##\nabla \mathscr{L} (x^∗,y^∗,λ^∗) = 0##

Now, I want to classify my triplets as max/min/saddle points, using the positive/negative definiteness of the Hessian like I have been doing for unconstrained optimization, so I compute what I think is the Hessian of the Lagrangian:

$$H_{\mathscr{L}}(x,y,λ)= \begin{pmatrix} 12x^2 - 2\lambda & 0 \\ 0 & -12y^2 - 4\lambda \end{pmatrix}$$

Evaluating the Hessian for my first triplet ##(0,\pm \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},−\frac{1}{2})## gives me:

$$H_{\mathscr{L}}(0,\pm \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},−\frac{1}{2}) = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & - 4\end{pmatrix}$$

This matrix is diagonal, meaning that we immediately read its eigenvalues on the diagonal: ##\lambda_1 = 1 > 0## and ##\lambda_2 = -4 < 0##. A positive/negative definite matrix has only positive/negative eigenvalues, thus I conclude that this matrix is neither, due to its eigenvalues' opposite signs.

When I was studying unconstrained optimization, I learned that we have in this case a saddle point, so I would like to think that the points ##(0,\pm \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2})## are both saddle points for my function f, however, the solution to this problem affirms these points are minimums, using the following argument:

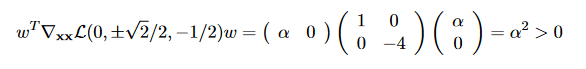

Using the fact that ##\nabla g(x,y) = (0,\pm \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2})## and that ##w^T \nabla g(x,y) = 0## if and only if ##w = (\alpha, 0), \alpha \in \mathbb{R}^{\ast}##

I thought that it was enough to check for the definiteness of the Hessian, and now I am really confused...

Here are my questions:

Edit: PF destroyed my LaTeX formatting.

I am using the Lagrange multipliers method to find the extremums of ##f(x,y)## subjected to the constraint ##g(x,y)##, an ellipse.

So far, I have successfully identified several triplets ##(x^∗,y^∗,λ^∗)## such that each triplet is a stationary point for the Lagrangian: ##\nabla \mathscr{L} (x^∗,y^∗,λ^∗) = 0##

Now, I want to classify my triplets as max/min/saddle points, using the positive/negative definiteness of the Hessian like I have been doing for unconstrained optimization, so I compute what I think is the Hessian of the Lagrangian:

$$H_{\mathscr{L}}(x,y,λ)= \begin{pmatrix} 12x^2 - 2\lambda & 0 \\ 0 & -12y^2 - 4\lambda \end{pmatrix}$$

Evaluating the Hessian for my first triplet ##(0,\pm \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},−\frac{1}{2})## gives me:

$$H_{\mathscr{L}}(0,\pm \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2},−\frac{1}{2}) = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & - 4\end{pmatrix}$$

This matrix is diagonal, meaning that we immediately read its eigenvalues on the diagonal: ##\lambda_1 = 1 > 0## and ##\lambda_2 = -4 < 0##. A positive/negative definite matrix has only positive/negative eigenvalues, thus I conclude that this matrix is neither, due to its eigenvalues' opposite signs.

When I was studying unconstrained optimization, I learned that we have in this case a saddle point, so I would like to think that the points ##(0,\pm \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2})## are both saddle points for my function f, however, the solution to this problem affirms these points are minimums, using the following argument:

Using the fact that ##\nabla g(x,y) = (0,\pm \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2})## and that ##w^T \nabla g(x,y) = 0## if and only if ##w = (\alpha, 0), \alpha \in \mathbb{R}^{\ast}##

I thought that it was enough to check for the definiteness of the Hessian, and now I am really confused...

Here are my questions:

- When is it enough to check the definiteness of the Hessian to classify stationnary points?

- Why is there this additional step in constrained optimization?

- What am I missing?

Edit: PF destroyed my LaTeX formatting.

Last edited by a moderator: