Discussion Overview

The discussion revolves around finding an efficient algorithm to determine whether an odd integer is prime, specifically through the use of polynomial congruences and computational cost analysis. Participants explore the implications of choosing a polynomial modulus and the efficiency of various algorithms, including recursive methods and fast exponentiation.

Discussion Character

- Technical explanation

- Mathematical reasoning

- Debate/contested

Main Points Raised

- One participant proposes testing the congruence $(X+a)^n \equiv X^n+a$ modulo a polynomial $X^r-1$ to check for primality.

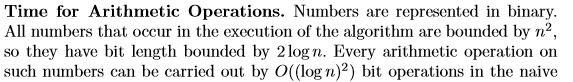

- Another participant questions the meaning of $r$ being $O((\log{n})^c)$ and its implications for computational cost.

- There is a suggestion to use a recursive algorithm based on squaring to evaluate polynomials, with a focus on determining the computational cost $f(n,r)$.

- Participants discuss the potential use of the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) for polynomial multiplication, noting its time complexity of $O(d \log{d})$.

- One participant proposes a recursive relation for $f(n,n)$ based on whether $n$ is even or odd, while others refine this relation.

- There is a debate over whether $r$ should be treated as a constant or if it can vary, with some suggesting it must be chosen cleverly to maintain polynomial cost.

- Participants explore the implications of polynomial degrees and the operations involved in multiplying polynomials, particularly in the context of the FFT.

- Concerns are raised about the degree of the resulting polynomial and the need for initial conditions in solving recurrence relations.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express differing views on the interpretation of $r$ and its role in the computational cost, leading to unresolved questions about the implications of choosing $r$ as $O((\log{n})^c)$. There is no consensus on the best approach to analyze the computational cost or the exact nature of the polynomial operations involved.

Contextual Notes

Limitations include the dependence on the choice of $r$, the assumptions about polynomial degrees, and the unresolved nature of the computational cost analysis. The discussion also highlights the need for initial conditions in recurrence relations, which remains unaddressed.