Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I have been thinking around the definition of a unit in a ring and trying to fully understand why the definition is the way it is ... ...

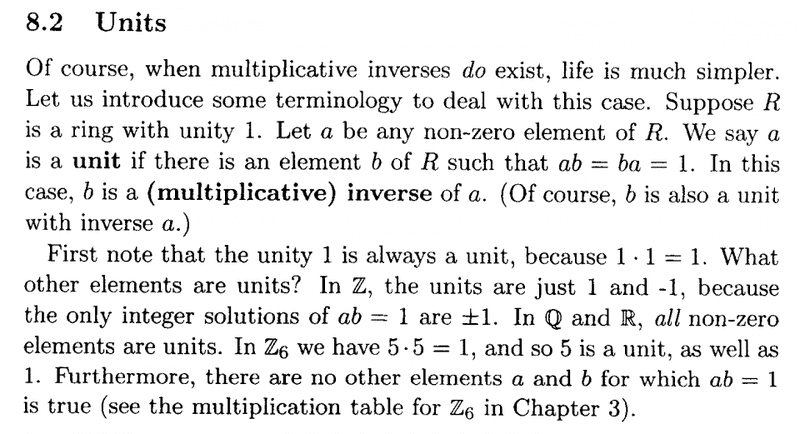

Marlow Anderson and Todd Feil, in their book "A First Course in Abstract Algebra: Rings, Groups and Fields (Second Edition), introduce units in a ring with 1 in the following way ... ...

So ... an element ##a## of a ring ##R## with ##1## is a unit if there is an element ##b## of ##R## such that

##ab = ba = 1## ... ...So ... if, in the case where ##R## was noncommutative, ##ab = 1## and ##ba \neq 1## then ##a## would not be a unit ... is that right?

Presumably it is not 'useful' to describe ##a## as a 'left unit' in such a case ... that is, presumably one-sided units are not worth defining ... is that right?

Could someone please comment on and perhaps clarify/correct the above ...Hope someone can help ...

Peter

Marlow Anderson and Todd Feil, in their book "A First Course in Abstract Algebra: Rings, Groups and Fields (Second Edition), introduce units in a ring with 1 in the following way ... ...

So ... an element ##a## of a ring ##R## with ##1## is a unit if there is an element ##b## of ##R## such that

##ab = ba = 1## ... ...So ... if, in the case where ##R## was noncommutative, ##ab = 1## and ##ba \neq 1## then ##a## would not be a unit ... is that right?

Presumably it is not 'useful' to describe ##a## as a 'left unit' in such a case ... that is, presumably one-sided units are not worth defining ... is that right?

Could someone please comment on and perhaps clarify/correct the above ...Hope someone can help ...

Peter