gnits

- 137

- 46

- Homework Statement

- To prove that three forces are in equilibrium

- Relevant Equations

- Equating of forces

Could I please ask for help regarding the following question:

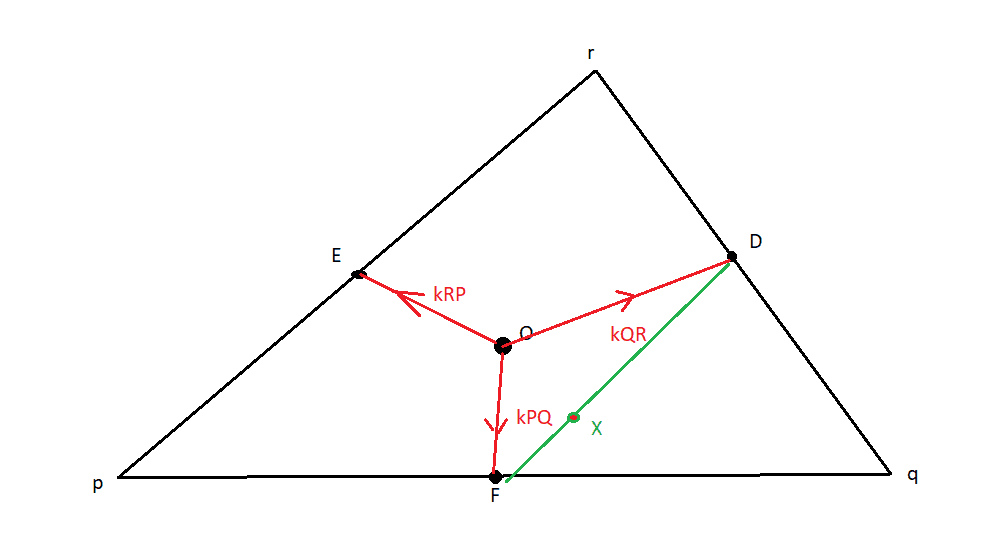

D, E and F are the midpoints of the sides QR, RP and PQ respectively of triangle PQR whose circumcenter is O. Forces of magnitude kQR, kRP and kPQ act at O in directions ##\overrightarrow{OD}##, ##\overrightarrow{OE}## and ##\overrightarrow{OF}## respectively.

Prove that the forces are in equilibrium.

I am allowed to make use of the following fact, (although I am free to answer the question any other way):

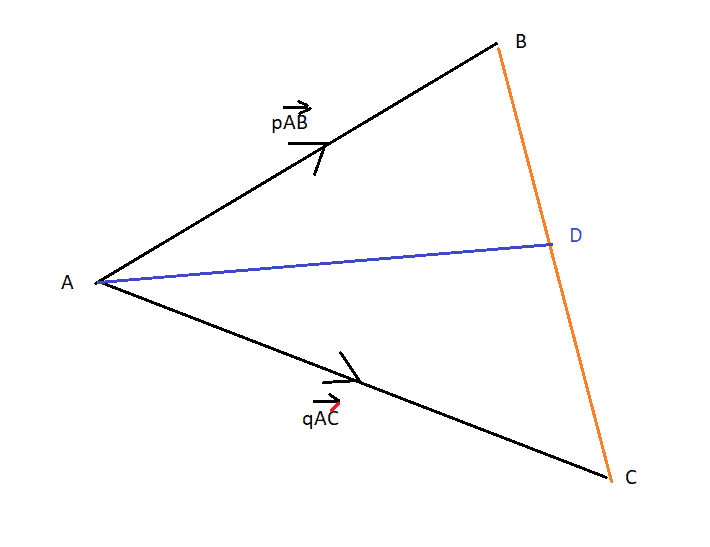

With both forces going away from A we have:

##p\overrightarrow{AB}## + ##q\overrightarrow{AC}## = ##(p+q)\overrightarrow{AD}##

where

##BD:DC = q:p##

Here's a diagram for the problem (the green stuff is referenced in my solution below where I attempt to apply the above fact).

I was hoping to show that the kPQ and kQR forces combined to give a force which was opposite (so ##\overrightarrow{OX}## would be opposite to ##\overrightarrow{OE}## ) and of equal size to the kRP force by using the above fact. Well straight off I see that this would give a force of magnitude k(QR + PQ) which I would need to be equal to kRP, and I can't see how that can be so.

Thanks for any help,

Mitch.

D, E and F are the midpoints of the sides QR, RP and PQ respectively of triangle PQR whose circumcenter is O. Forces of magnitude kQR, kRP and kPQ act at O in directions ##\overrightarrow{OD}##, ##\overrightarrow{OE}## and ##\overrightarrow{OF}## respectively.

Prove that the forces are in equilibrium.

I am allowed to make use of the following fact, (although I am free to answer the question any other way):

With both forces going away from A we have:

##p\overrightarrow{AB}## + ##q\overrightarrow{AC}## = ##(p+q)\overrightarrow{AD}##

where

##BD:DC = q:p##

Here's a diagram for the problem (the green stuff is referenced in my solution below where I attempt to apply the above fact).

I was hoping to show that the kPQ and kQR forces combined to give a force which was opposite (so ##\overrightarrow{OX}## would be opposite to ##\overrightarrow{OE}## ) and of equal size to the kRP force by using the above fact. Well straight off I see that this would give a force of magnitude k(QR + PQ) which I would need to be equal to kRP, and I can't see how that can be so.

Thanks for any help,

Mitch.