Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

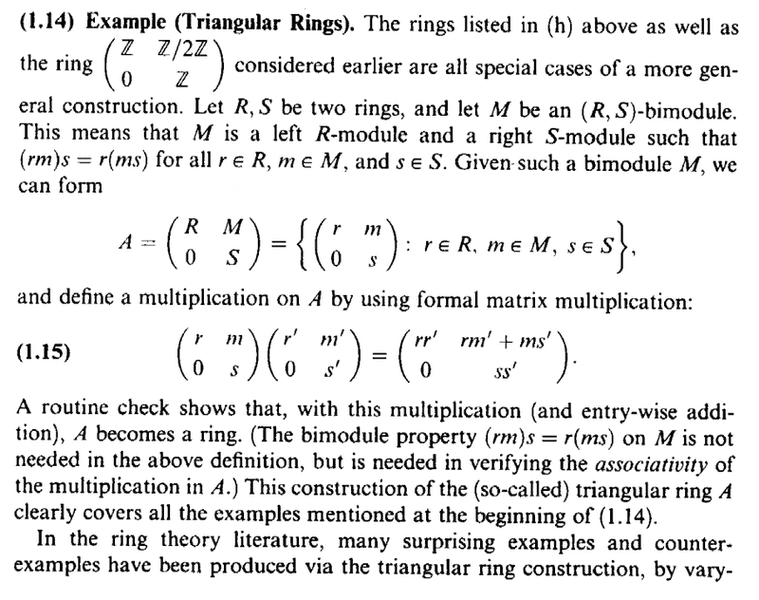

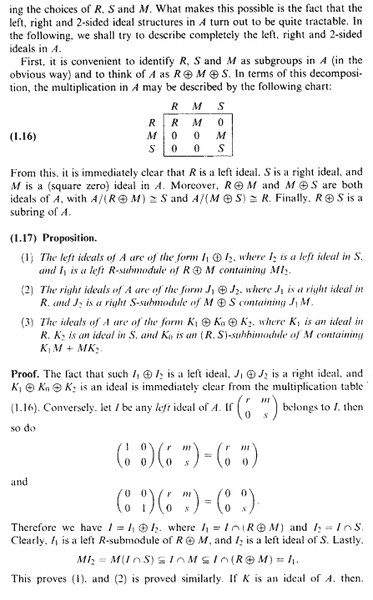

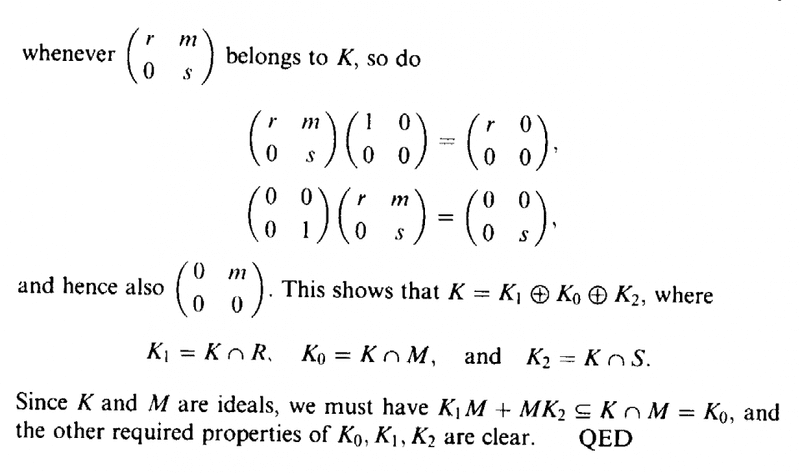

I am reading T. Y. Lam's book, "A First Course in Noncommutative Rings" (Second Edition) and am currently focussed on Section 1:Basic Terminology and Examples ...

I need help with Part (1) of Proposition 1.17 ... ...

Proposition 1.17 (together with related material from Example 1.14 reads as follows:

Can someone please help me to prove Part (1) of the proposition ... that is that ##I_1 \oplus I_2## is a left ideal of A ... ...

Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter

I need help with Part (1) of Proposition 1.17 ... ...

Proposition 1.17 (together with related material from Example 1.14 reads as follows:

Can someone please help me to prove Part (1) of the proposition ... that is that ##I_1 \oplus I_2## is a left ideal of A ... ...

Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter