Discussion Overview

The discussion revolves around questions related to black body radiation, specifically focusing on the concepts of spectral radiance and photon flux. Participants explore the definitions, implications, and calculations associated with these concepts, including their relationships to energy and photon number across different wavelengths.

Discussion Character

- Exploratory

- Technical explanation

- Debate/contested

Main Points Raised

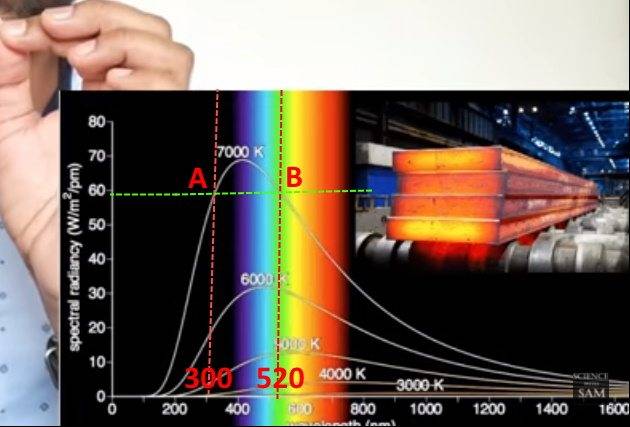

- One participant questions whether the spectral radiance measurement at 7000K is the same for both 300 nm and 520 nm wavelengths.

- Another participant confirms that spectral radiance is not the number of photons but rather the radiated energy per square meter, per unit wavelength interval, and per unit solid angle.

- It is noted that the photon flux differs at various wavelengths due to the energy differences of photons at those wavelengths.

- Participants discuss how to calculate photon flux from spectral radiance by dividing by the energy per photon.

- One participant emphasizes the importance of gauge-invariant quantities in physical interpretations, arguing that naive photon number density is gauge-dependent and does not fulfill microcausality conditions.

- Another participant challenges the definition of photon flux and energy per photon, stating that these cannot represent actual numbers due to the quantum state of the electromagnetic field.

- There is a mention of the Poynting vector as a measure of observable intensity, distinguishing it from theoretical constructs of photon number.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express differing views on the interpretation of photon flux and the physical meaning of photon number. While some agree on the definitions of spectral radiance and its implications, others contest the validity of using photon number in certain contexts, indicating a lack of consensus on these points.

Contextual Notes

Participants highlight the limitations of using photon number as a measure due to its dependence on gauge conditions and the quantum state of the electromagnetic field. The discussion also reflects the complexity of relating theoretical constructs to measurable quantities in physics.

Who May Find This Useful

This discussion may be of interest to those studying black body radiation, quantum mechanics, and the interpretation of physical observables in electromagnetic theory.