NoahsArk

Gold Member

- 258

- 24

- TL;DR

- Need help understanding what a basis of a vector space is

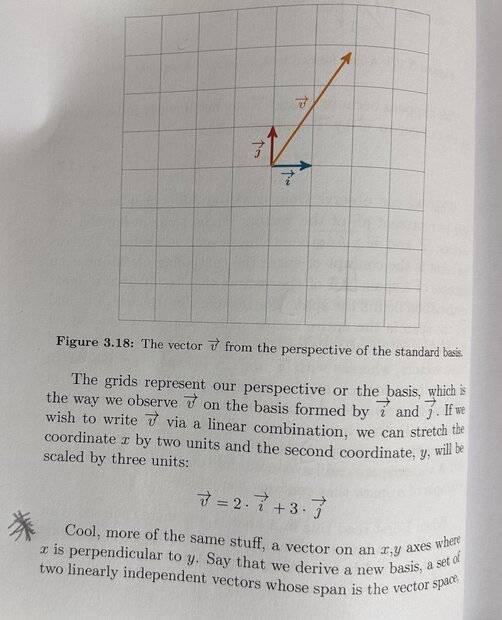

In the book I'm reading, Before Machine Learning, by Jorge Brasil, I'm on the section that introduces bases for vector spaces. The author gives the example of a vector space with two vectors ##\vec i## and ##\vec j## forming the basis where ##\vec i = (1,0)## and ##\vec j = (0,1)## He then says if we want to write a vector ## \vec v ## as a linear combination, we can write it as 2 x ##\vec i## + 3 x ##\vec j##. I am attaching the picture of this part of the book along with the diagram here:

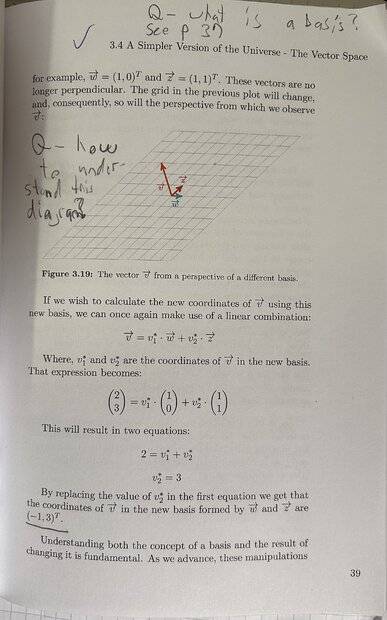

So far this doesn't seem too complicated, but then the author introduces a new basis which is formed by the vectors ##\vec w##, and ##\vec z## where ##\vec w = (1,0)## and ##\vec z = (1,1) ## He then shows a diagram representing this new basis which I don't understand- I'm pasting a picture of it here:

It appears that he has created a new coordinate plane by slanting the y axis. He has not labeled the coordinates of this plane, though, which is one reason that it's hard to understand. The vectors ## \vec w## and ##\vec z## that he's drawn on it, although he stated that they are supposed to have the coordinates (1,0) and (1,1) respectively, ## \vec z ## appears to have the coordinates (0,1) (like ## \vec j ##) although the author said ## \vec z ## is supposed to have coordinates (1,1). How to make sense of this diagram? ## \vec v ## on this diagram appears to have coordinates (-4, 3) which I don't think the author intended.

The author then says that if we want to calculate the coordinates of ##\vec v## in this new basis, we will need to find the scalars to multiply ##\vec w## and ##\vec z## by so that when we add these two vectors we get ##\vec v##. He then concludes, using the steps in the picture, that the coordinates of ##\vec v## in this basis will be (-1, 3). However, -1 and 3 to me seem not to be coordinates of a vector, but rather two scalars that we need to multiply ##\vec w## and ## \vec z ## by to get ## \vec v ## which has coordinates (2,3). Please let me know what I'm missing. Thanks.

So far this doesn't seem too complicated, but then the author introduces a new basis which is formed by the vectors ##\vec w##, and ##\vec z## where ##\vec w = (1,0)## and ##\vec z = (1,1) ## He then shows a diagram representing this new basis which I don't understand- I'm pasting a picture of it here:

It appears that he has created a new coordinate plane by slanting the y axis. He has not labeled the coordinates of this plane, though, which is one reason that it's hard to understand. The vectors ## \vec w## and ##\vec z## that he's drawn on it, although he stated that they are supposed to have the coordinates (1,0) and (1,1) respectively, ## \vec z ## appears to have the coordinates (0,1) (like ## \vec j ##) although the author said ## \vec z ## is supposed to have coordinates (1,1). How to make sense of this diagram? ## \vec v ## on this diagram appears to have coordinates (-4, 3) which I don't think the author intended.

The author then says that if we want to calculate the coordinates of ##\vec v## in this new basis, we will need to find the scalars to multiply ##\vec w## and ##\vec z## by so that when we add these two vectors we get ##\vec v##. He then concludes, using the steps in the picture, that the coordinates of ##\vec v## in this basis will be (-1, 3). However, -1 and 3 to me seem not to be coordinates of a vector, but rather two scalars that we need to multiply ##\vec w## and ## \vec z ## by to get ## \vec v ## which has coordinates (2,3). Please let me know what I'm missing. Thanks.