eipiplusone

- 9

- 0

Hi,

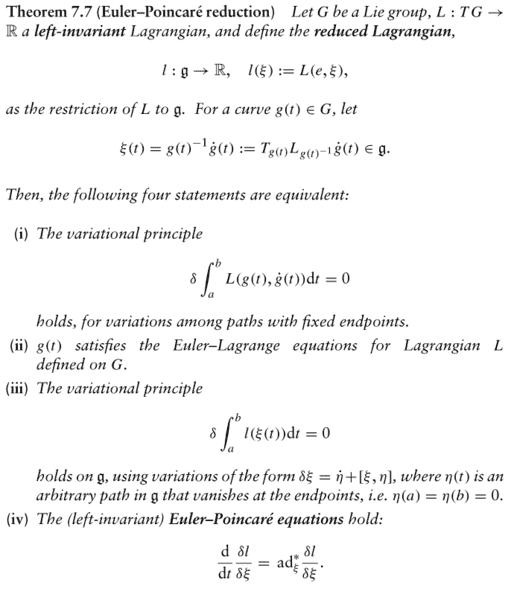

I'm trying to understand the Euler-Poincare equations, which reduce the Euler-Lagrange equations for certain Lagrangians on a Lie group. I'm reading Darryl Holm's "Geometric mechanics and symmetry", where he suddenly uses what seems to be a variational derivative, which I'm having a hard time understanding. The Euler-Poincare reduction theorem (and equation) goes as follows:

It is the ##\frac{\delta l}{\delta \xi}## - derivative which I'm guessing is a variational derivative. It must be a covector, and in computations it seems to reduce to partial derivatives of ##l## wrt. ##\xi## (in suitable coordinates) - I have also seen other sources where the EP-equation is stated in terms of ##\frac{\partial l}{\partial \xi}## instead of the abovementioned.

He defines it in two different ways. The first definition is found in one of the later chapters of the book (and it seems to be in a more general setting):

And in another book ("Geometric mechanics - part 2") he defines it as:

My questions are:

- which definition should I focus on?

- Is the pairing in the latter definition the usual covector-vector pairing?

Any explanations, hints or references would be greatly appreciated! Thanks.

<mentor: fix latex>

I'm trying to understand the Euler-Poincare equations, which reduce the Euler-Lagrange equations for certain Lagrangians on a Lie group. I'm reading Darryl Holm's "Geometric mechanics and symmetry", where he suddenly uses what seems to be a variational derivative, which I'm having a hard time understanding. The Euler-Poincare reduction theorem (and equation) goes as follows:

It is the ##\frac{\delta l}{\delta \xi}## - derivative which I'm guessing is a variational derivative. It must be a covector, and in computations it seems to reduce to partial derivatives of ##l## wrt. ##\xi## (in suitable coordinates) - I have also seen other sources where the EP-equation is stated in terms of ##\frac{\partial l}{\partial \xi}## instead of the abovementioned.

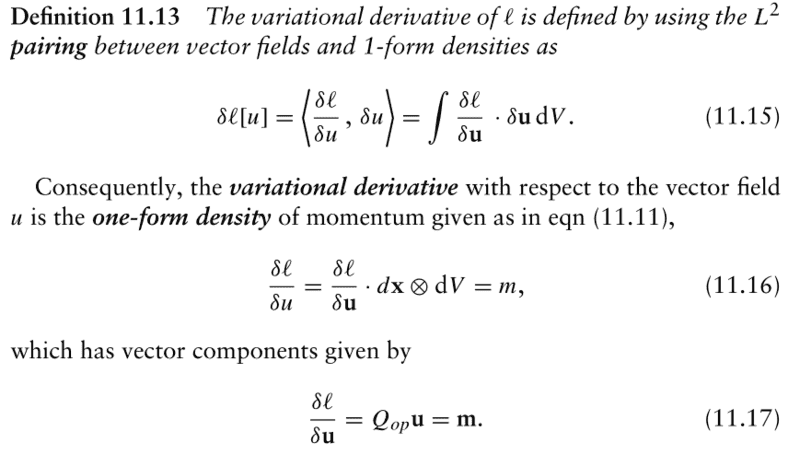

He defines it in two different ways. The first definition is found in one of the later chapters of the book (and it seems to be in a more general setting):

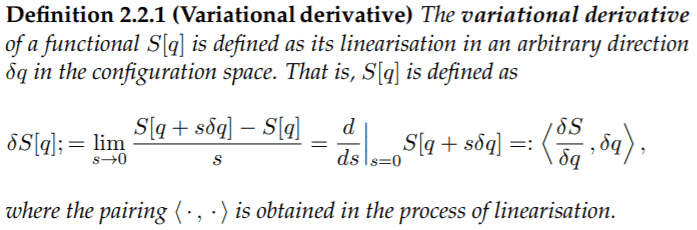

And in another book ("Geometric mechanics - part 2") he defines it as:

My questions are:

- which definition should I focus on?

- Is the pairing in the latter definition the usual covector-vector pairing?

Any explanations, hints or references would be greatly appreciated! Thanks.

<mentor: fix latex>

Attachments

-

upload_2019-2-19_20-45-5.png26.4 KB · Views: 582

upload_2019-2-19_20-45-5.png26.4 KB · Views: 582 -

upload_2019-2-19_20-47-36.png707 bytes · Views: 533

upload_2019-2-19_20-47-36.png707 bytes · Views: 533 -

upload_2019-2-19_20-53-28.png22.9 KB · Views: 922

upload_2019-2-19_20-53-28.png22.9 KB · Views: 922 -

upload_2019-2-19_20-58-44.png10.8 KB · Views: 537

upload_2019-2-19_20-58-44.png10.8 KB · Views: 537 -

upload_2019-2-19_21-5-6.png23.7 KB · Views: 1,244

upload_2019-2-19_21-5-6.png23.7 KB · Views: 1,244 -

upload_2019-2-19_21-10-26.png23.2 KB · Views: 1,008

upload_2019-2-19_21-10-26.png23.2 KB · Views: 1,008

Last edited by a moderator: