baseballfan_ny

- 92

- 23

- Homework Statement

- Get a 4th order taylor approximation for $$ f(p) = (1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac 1 2} $$

- Relevant Equations

- $$\sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac {f^{(n)}(a) (x-a)^n} {n!}$$ around a = 0

So I just followed Taylor's formula and got the four derivatives at p = 0

##f^{(0)}(p) = (1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac 1 2} ##

##f^{(0)}(0) = 1 ##

## f^{(1)}(p) = \frac {p} {m^2c^2}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-1} 2} ##

## f^{(1)}(0) = 0 ##

## f^{(2)}(p) = \frac {1} {m^2c^2}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-1} 2} - \frac {p^2} {m^4c^4}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-3} 2} ##

## f^{(2)}(0) = \frac {1} {m^2c^2} ##

## f^{(3)}(p) = \frac {p} {m^4c^4}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-3} 2} - \frac {3p^3} {m^6c^6}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-5} 2} ##

## f^{(3)}(0) = 0##

## f^{(4)}(p) = \frac {1} {m^4c^4}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-3} 2} +... ## (terms that are 0 when p = 0)

## f^{(4)}(0) = \frac {1} {m^4c^4} ##

Now that would give me $$ f(p) = 1 + \frac {p^2} {2! m^2c^2} + \frac {p^4} {4! m^4c^4} $$

$$ f(p) = 1 + \frac {p^2} {2m^2c^2} + \frac {p^4} {24m^4c^4} $$

But that's not right. The answer key has the following answer (and so does Wolfram) $$ f(p) = 1 + \frac {p^2} {2m^2c^2} - \frac {p^4} {8m^4c^4} $$

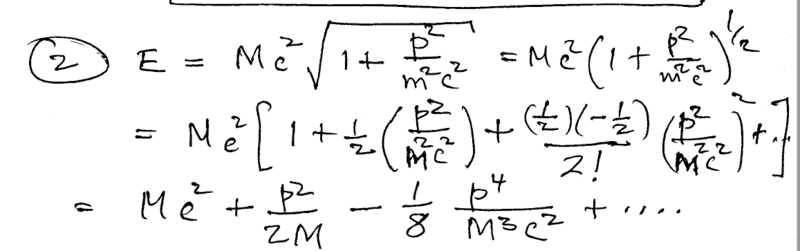

A picture of the answer key soln is below. Ignore the factor of ##Mc^2## outside the approximation.

I noticed that the answer doesn't even get any of the derivatives equal to 0, and I was getting all the odd derivatives equal to 0. That makes me think I'm applying Taylor's formula incorrectly and it's more than just an algebra mistake?

##f^{(0)}(p) = (1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac 1 2} ##

##f^{(0)}(0) = 1 ##

## f^{(1)}(p) = \frac {p} {m^2c^2}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-1} 2} ##

## f^{(1)}(0) = 0 ##

## f^{(2)}(p) = \frac {1} {m^2c^2}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-1} 2} - \frac {p^2} {m^4c^4}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-3} 2} ##

## f^{(2)}(0) = \frac {1} {m^2c^2} ##

## f^{(3)}(p) = \frac {p} {m^4c^4}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-3} 2} - \frac {3p^3} {m^6c^6}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-5} 2} ##

## f^{(3)}(0) = 0##

## f^{(4)}(p) = \frac {1} {m^4c^4}(1 + \frac {p^2} {m^2c^2})^{\frac {-3} 2} +... ## (terms that are 0 when p = 0)

## f^{(4)}(0) = \frac {1} {m^4c^4} ##

Now that would give me $$ f(p) = 1 + \frac {p^2} {2! m^2c^2} + \frac {p^4} {4! m^4c^4} $$

$$ f(p) = 1 + \frac {p^2} {2m^2c^2} + \frac {p^4} {24m^4c^4} $$

But that's not right. The answer key has the following answer (and so does Wolfram) $$ f(p) = 1 + \frac {p^2} {2m^2c^2} - \frac {p^4} {8m^4c^4} $$

A picture of the answer key soln is below. Ignore the factor of ##Mc^2## outside the approximation.

I noticed that the answer doesn't even get any of the derivatives equal to 0, and I was getting all the odd derivatives equal to 0. That makes me think I'm applying Taylor's formula incorrectly and it's more than just an algebra mistake?