Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading Karl R. Stromberg's book: "An Introduction to Classical Real Analysis". ... ...

I am focused on Chapter 3: Limits and Continuity ... ...

I need help in order to fully understand the proof of Theorem 3.55 on page 110 ... ... Theorem 3.55 and its proof read as follows:

View attachment 9165

At the start of the second paragraph of the above proof by Stromberg we read the following:

" ... ...Since $$A_1^{ - \ \circ } = \emptyset$$, we can choose $$x_1$$ in the open set $$V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ and then we can choose $$0 \lt r_1 \lt 1$$ such that $$B_{ r_1 } ( x_1 )^{ - } \subset V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ [ check that $$B_r (x)^{ - } \subset B_{ 2r } (x) $$ ] ... ...My questions are as follows:Question 1

Can someone explain and demonstrate why/how it is that $$A_1^{ - \ \circ } = \emptyset$$ means that we can choose $$x_1$$ in the open set $$V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ ... how are we (rigorously) sure this is true ... ?

Question 2

How/why can we choose $$0 \lt r_1 \lt 1$$ such that $$B_{ r_1 } ( x_1 )^{ - } \subset V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ ... ?

... and why are we checking that $$B_r (x)^{ - } \subset B_{ 2r } (x)$$ ... ... ?

*** EDIT ***

My thoughts on Question 2 ...

Since $$V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ is open ... $$\exists \ r_1$$ such that $$B_{ r_1 } ( x_1 ) \subset V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ ...

... BUT ... how do we formally and rigorously show that ...

... we can choose an $$r_1$$ such that the closure of $$B_{ r_1 } ( x_1 )$$ is a subset of $$V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ ...

... (intuitively I think we just choose $$r_1$$ somewhat smaller yet ...)

... and further why is Stromberg talking about $$r_1$$ between $$0$$ and $$1$$ ...?

Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter

==================================================================================

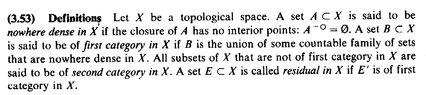

The definitions of nowhere dense, first and second category and residual are relevant ... so I am providing Stromberg's definitions ... as follows:

View attachment 9166

Stromberg's terminology and notation associated with the basic notions of topological spaces are relevant to the above post ... so I am providing the text of the same ... as follows:

View attachment 9167Hope that helps ...

Peter

I am focused on Chapter 3: Limits and Continuity ... ...

I need help in order to fully understand the proof of Theorem 3.55 on page 110 ... ... Theorem 3.55 and its proof read as follows:

View attachment 9165

At the start of the second paragraph of the above proof by Stromberg we read the following:

" ... ...Since $$A_1^{ - \ \circ } = \emptyset$$, we can choose $$x_1$$ in the open set $$V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ and then we can choose $$0 \lt r_1 \lt 1$$ such that $$B_{ r_1 } ( x_1 )^{ - } \subset V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ [ check that $$B_r (x)^{ - } \subset B_{ 2r } (x) $$ ] ... ...My questions are as follows:Question 1

Can someone explain and demonstrate why/how it is that $$A_1^{ - \ \circ } = \emptyset$$ means that we can choose $$x_1$$ in the open set $$V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ ... how are we (rigorously) sure this is true ... ?

Question 2

How/why can we choose $$0 \lt r_1 \lt 1$$ such that $$B_{ r_1 } ( x_1 )^{ - } \subset V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ ... ?

... and why are we checking that $$B_r (x)^{ - } \subset B_{ 2r } (x)$$ ... ... ?

*** EDIT ***

My thoughts on Question 2 ...

Since $$V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ is open ... $$\exists \ r_1$$ such that $$B_{ r_1 } ( x_1 ) \subset V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ ...

... BUT ... how do we formally and rigorously show that ...

... we can choose an $$r_1$$ such that the closure of $$B_{ r_1 } ( x_1 )$$ is a subset of $$V$$ \ $$A_1^{ - }$$ ...

... (intuitively I think we just choose $$r_1$$ somewhat smaller yet ...)

... and further why is Stromberg talking about $$r_1$$ between $$0$$ and $$1$$ ...?

Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter

==================================================================================

The definitions of nowhere dense, first and second category and residual are relevant ... so I am providing Stromberg's definitions ... as follows:

View attachment 9166

Stromberg's terminology and notation associated with the basic notions of topological spaces are relevant to the above post ... so I am providing the text of the same ... as follows:

View attachment 9167Hope that helps ...

Peter

Attachments

Last edited: