I think it is very important to get some order in thinking about this problem before you start. First of all you deal with classical electrodynamics. If you read the word "classical" then it's utmost always clear that nowhere Planck's constant ##h=2 \pi \hbar## can occur, because this quantity is introduced into physics only within quantum theory. So don't confuse yourself with thinking about electromagnetic problems, which deal with classical electromagnetism, in terms of "photons" or other quantum concepts. Photons are anyway closer to classical wave theory than classical mechanics, i.e., the most simple picture of electromagnetic phenomena is the field picture anyway. If you have to deal with quantum theory of electromagnetic phenomena, i.e., quantum electrodynamics, you have to study quantum electrodynamics (QED), which is more advanced than classical electrodynamics, and you need a very good understanding of classical electrodynamics first, before starting studying QED.

Now you deal with general fields within classical electrodynamics, not special solutions thereof. So you cannot assume that ##\vec{E}## and ##\vec{B}## are perpendicular to each other. In the context of waves this is only the case for plane-wave modes, which are only solutions of Maxwell's equations in source-free regions (i.e., in regions without currents and charges).

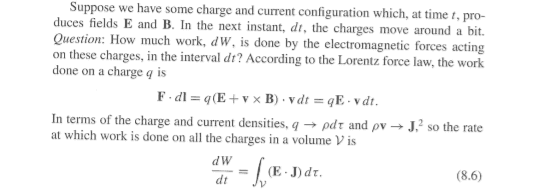

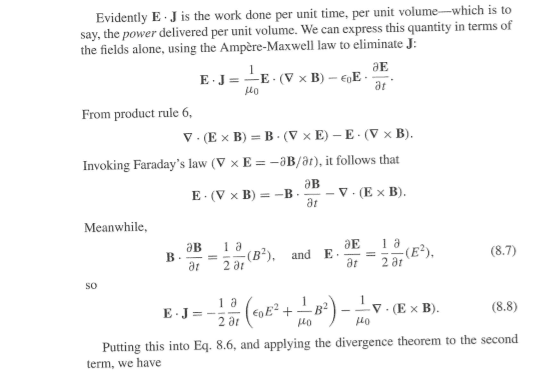

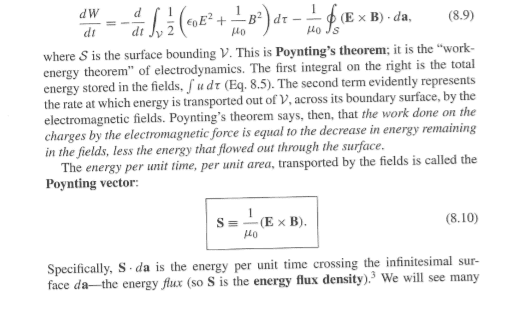

What's supposed to be calculated is the energy balance of electromagnetic fields interacting with charges and currents in general, starting from the energy distribution and flow of the electromagnetic field. Physically it's clear what must come out: If there were no charge-current distributions around the total energy of the electromagnetic field would be conserved, and in local form this means the energy density of the em. field

$$u_{\text{em}}=\frac{\epsilon_0}{2} \vec{E}^2 + \frac{1}{2 \mu_0} \vec{B}^2$$

and the energy-current density

$$\vec{S}_{\text{em}}=\frac{1}{\mu_0} \vec{E} \times \vec{B}$$

would obey the continuity equation, expressing the fact that the only way energy can changing within a volume if energy is transported through its boundary surface, i.e.,

$$\partial_t u_{\text{em}} + \vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{S}_{\text{em}}=0 \quad \text{for} \quad \rho=0, \quad \vec{j}=0.$$

If however charges and currents are present the field also interacts with them and the charges get accelerated through this interaction. Thus you must get something on the right-hand side of the continuity equation, i.e., the energy per unit time transferred to the charges. Since the force per unit volume is $$\vec{f}=\rho (\vec{E} + \vec{v} \times \vec{B})$$, the power per unit volume transferred to the charges is $$\vec{v} \cdot \vec{f}=\rho \vec{v} \cdot \vec{E}=\vec{j} \cdot \vec{E}$$. From the point of view of the em. field this is "lost energy per time and volume", i.e., you must get

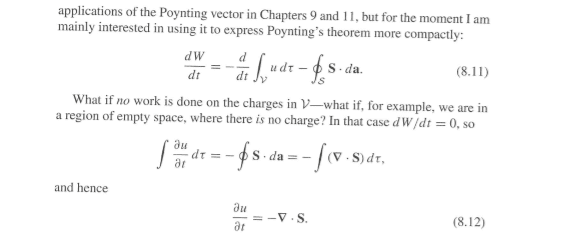

$$\partial_t u_{\text{em}} + \vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{S}_{\text{em}}=-\vec{j} \cdot \vec{E}.$$

This is "Poynting's theorem", and you can prove it with help of the Maxwell equations. This is what Griffiths demonstrates in #1.

The time derivative of the em. energy density is straight-forward to calculate. You only need

$$\partial_t (\vec{E}^2)=2 \vec{E} \cdot \partial_t \vec{E}, \quad \partial_t (\vec{B}^2)=2 \vec{E} \cdot \partial_t\vec{B}.$$

The calculation of ##\vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{S}## is easier in the Ricci calculus, where you deal with the components and with partial derivatives rather than with the vector notation and nabla calculus:

$$\mu_0 \vec{S}=\vec{E} \times \vec{B}\; \Rightarrow \; \mu_0 S_j =\epsilon_{jkl} E_k B_l.$$

Here we imply Einstein's summation convention over repeated indices, and ##\epsilon_{jkl}## is the totally antisymmetric Levi-Civita symbol with ##\epsilon_{123}=1##. Now

$$\mu_0 \vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{S}_{\text{em}}=\partial_j (\epsilon_{jkl} E_k B_l)=\epsilon_{jkl} (B_l \partial_j E_k + E_k \partial_j B_l)=\vec{B} \cdot (\vec{\nabla} \times \vec{E})-\vec{E} \cdot (\vec{\nabla} \times \vec{B}).$$

This leads to

$$\partial_t u_{\text{em}}+\vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{S}_{\text{em}} = \epsilon_0 \vec{E} \cdot \partial_t \vec{E} + \frac{1}{\mu_0} \vec{B} \cdot \partial_t \vec{B} +\frac{1}{\mu_0} [ \vec{B} \cdot (\vec{\nabla} \times \vec{E})-\vec{E} \cdot (\vec{\nabla} \times \vec{B})].$$

Faraday's Law,

$$\vec{\nabla} \times \vec{E}=-\partial_t \vec{B}$$

cancels the 2nd against the 3rd term:

$$\partial_t u_{\text{em}}+\vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{S}_{\text{em}} =\epsilon_0 \vec{E} \cdot \partial_t \vec{E} - \frac{1}{\mu_0} \vec{E} \cdot (\vec{\nabla} \times \vec{B}).$$

However, the Maxwell-Ampere Law tells you that

$$\frac{1}{\mu_0} \vec{\nabla} \times \vec{B}= \vec{j} + \epsilon_0 \partial_t \vec{E}$$.

Plugging this into the previous equation finally gives

$$\partial_t u_{\text{em}}+\vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{S}_{\text{em}} =-\vec{j} \cdot \vec{E},$$

which is what we wanted to prove.