Maxi1995

- 14

- 0

Hello,

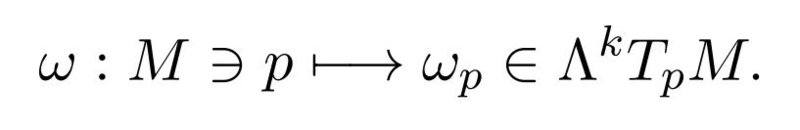

We defined a k-form on a smooth manifold M as a transfromation

Where the right space is the one of the alternating k-linear forms over the tangent space in p.

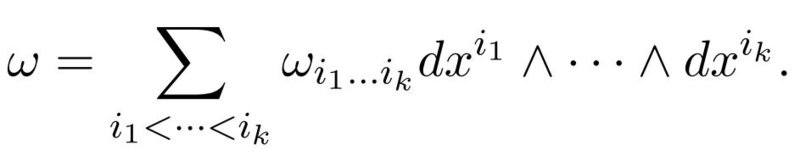

If we suppose we know, that we get a basis of this space by using the wedge-product and a basis of the dual space, then we might get for a given form:

Can someone explain to me what the coefficient in this linear combination is? I know that they are functions and in some cases scalars. But I don't know the cases. According to the definition at the beginning I suppose, that they are funtions for a given p and become scalars if we have argument values of the tangent space. Is this correct?

Greetings

Maxi

We defined a k-form on a smooth manifold M as a transfromation

Where the right space is the one of the alternating k-linear forms over the tangent space in p.

If we suppose we know, that we get a basis of this space by using the wedge-product and a basis of the dual space, then we might get for a given form:

Can someone explain to me what the coefficient in this linear combination is? I know that they are functions and in some cases scalars. But I don't know the cases. According to the definition at the beginning I suppose, that they are funtions for a given p and become scalars if we have argument values of the tangent space. Is this correct?

Greetings

Maxi