Discussion Overview

The discussion centers around the application of the Squeeze Theorem in a textbook example, specifically addressing the confusion regarding the treatment of limits when the variable x is stated to be non-zero but appears to be evaluated at zero. Participants explore the implications of continuity and the definitions of limits in this context.

Discussion Character

- Debate/contested

- Conceptual clarification

- Mathematical reasoning

Main Points Raised

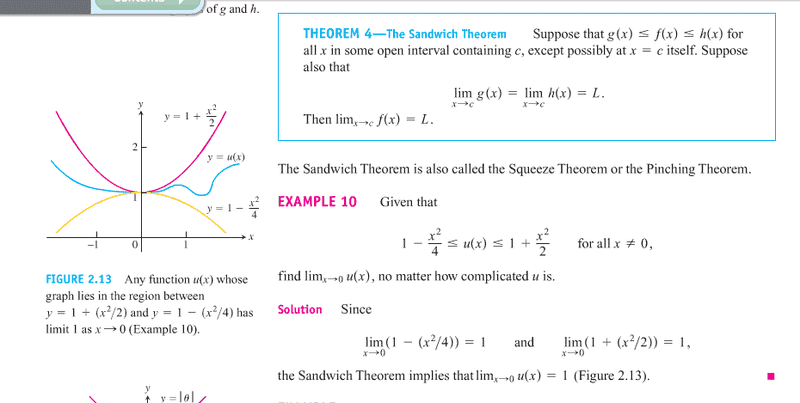

- One participant expresses confusion about why the example assumes x = 0 when it states "for all x ≠ 0," questioning the logic behind evaluating limits at zero.

- Another participant explains that if a function is continuous, limits can be evaluated by plugging in values, but if the function is not continuous at a point, the limit does not necessarily reflect the function's value at that point.

- A different viewpoint suggests that the limits of g(x) and h(x) being equal to 1 implies that x must be zero, raising concerns about the consistency of the example.

- One participant provides a specific example of a function u(x) that is defined differently at x = 0, illustrating that the limit can exist independently of the function's value at that point.

- Another participant emphasizes the importance of understanding that limits can be evaluated at points where the function is not defined, as long as the function behaves consistently around that point.

- Several participants acknowledge their own uncertainties about limits and continuity, indicating that the pace of their learning may contribute to their confusion.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants do not reach a consensus on the interpretation of the example. There are multiple competing views regarding the treatment of limits and continuity, and the discussion remains unresolved.

Contextual Notes

Some participants highlight the potential misunderstanding of limits and continuity, indicating that the definitions and conditions surrounding these concepts may not be fully grasped by all contributors.