Karl Karlsson

- 104

- 12

- Homework Statement

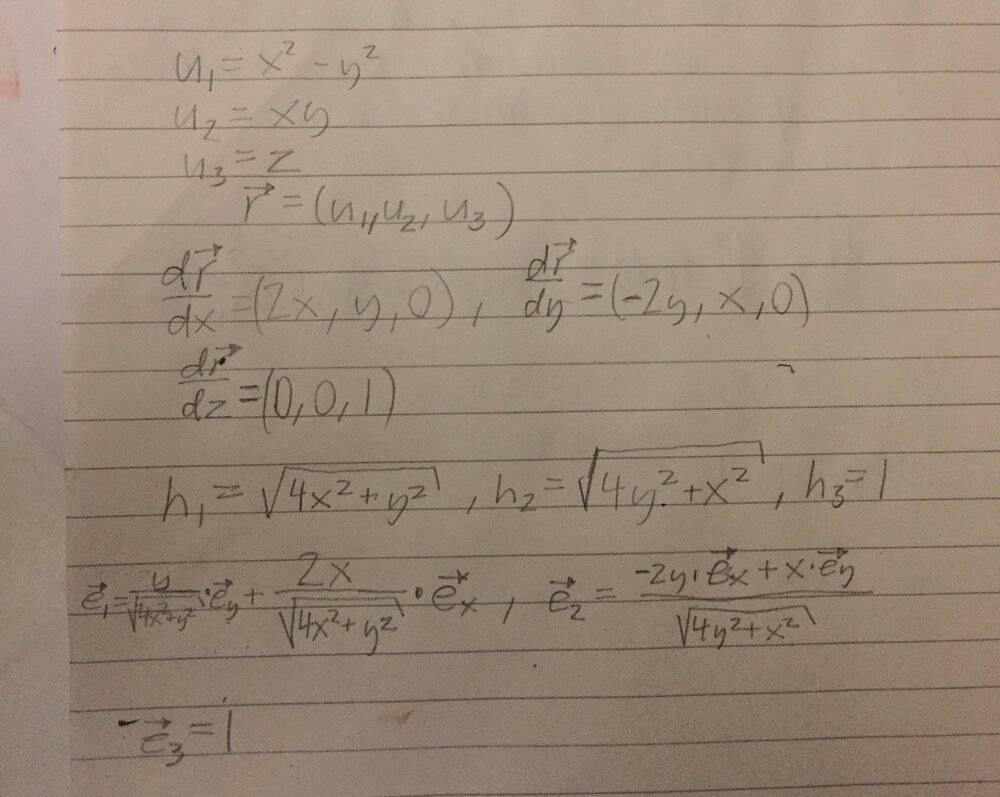

- Determine the standardized base vectors in the curvilinear coordinate system $$\begin{cases} u_1 = x^2-y^2 \\ u_2 = xy \\ u_3 = z\end{cases}$$

- Relevant Equations

- $$\begin{cases} u_1 = x^2-y^2 \\ u_2 = xy \\ u_3 = z\end{cases}$$

How I would have guessed you were supposed to solve it:

What you are supposed to do is just take the gradients of all the u:s and divide by the absolute value of the gradient? But what formula is that why is the way I did not the correct way to do it?

Thanks in advance!

What you are supposed to do is just take the gradients of all the u:s and divide by the absolute value of the gradient? But what formula is that why is the way I did not the correct way to do it?

Thanks in advance!