Discussion Overview

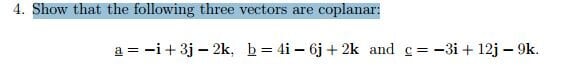

The discussion revolves around whether the condition of the triple product being zero, specifically $a \cdot (b \times c) = 0$, is sufficient to guarantee that the vectors $a$, $b$, and $c$ are coplanar. Participants explore the implications of this condition in the context of vector relationships and linear independence.

Discussion Character

Main Points Raised

- Some participants propose that if $a \cdot (b \times c) = 0$, then $a$ is orthogonal to the vector $b \times c$, which is orthogonal to both $b$ and $c$. However, they question how this leads to the conclusion that the vectors are coplanar.

- Others argue that if $b$ and $c$ are linearly independent, they span a plane, and thus $a$ must be a linear combination of $b$ and $c$, implying coplanarity.

- There is a discussion about the three possibilities for the vectors: being on the same line, in the same plane, or spanning the whole 3-dimensional space, with some participants questioning the sufficiency of the zero triple product to determine these cases.

- Some participants challenge the assertion that $a$ is parallel to $b$ and $c$, suggesting that this is not necessarily true and that $a$ could simply lie in the same plane as $b$ and $c$.

- Questions arise regarding the conditions under which two vectors are linearly independent and the implications of their cross product being non-zero.

- There is a clarification that a plane in $\mathbb{R}^3$ is not a subset of $\mathbb{R}^2$, but rather isomorphic to it, which adds complexity to the discussion about the nature of the vectors and their relationships.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express differing views on the implications of the zero triple product, with no consensus reached on whether it definitively guarantees coplanarity. The discussion remains unresolved regarding the conditions under which the vectors can be classified into the proposed categories.

Contextual Notes

Participants note limitations in their arguments, such as the dependence on definitions of linear independence and the implications of the cross product. There are also unresolved questions about the nature of the vectors and their relationships in three-dimensional space.