SUMMARY

The discussion centers on the derivation of the de Broglie relation, specifically addressing the integration constant 'c' in the equation p = ħk + c. Participants argue that symmetry considerations dictate that 'c' must equal zero, as changing the sign of momentum (p) necessitates a corresponding change in the wave number (k). The conversation also highlights the vector nature of k and p, emphasizing that the mean momentum is equal to ħ times the mean wavenumber, and discusses the implications of zero mean momentum on wave packet behavior.

PREREQUISITES

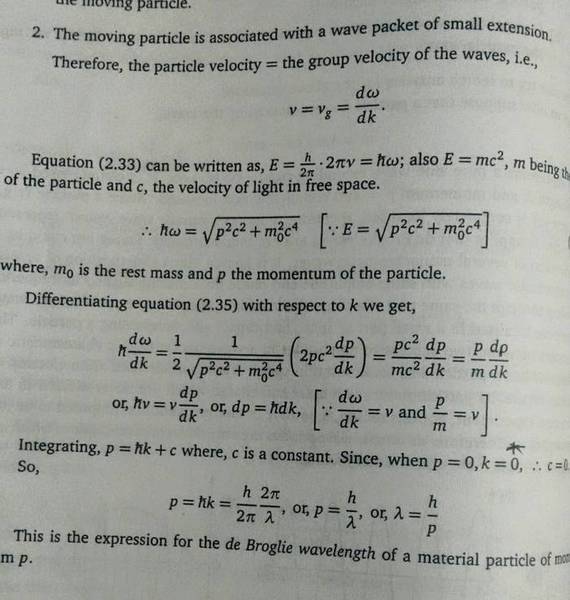

- Understanding of the de Broglie relation and its implications in quantum mechanics.

- Familiarity with wave packets and their properties in physics.

- Knowledge of vector quantities and their behavior under transformations.

- Basic grasp of group velocity and its calculation in wave mechanics.

NEXT STEPS

- Study the derivation of the de Broglie relation in detail using wave packets.

- Explore the concept of symmetry in physics and its applications in quantum mechanics.

- Learn about the mathematical treatment of group velocity and its implications in wave propagation.

- Investigate the relationship between momentum and wave number in various physical contexts.

USEFUL FOR

Students and professionals in physics, particularly those focusing on quantum mechanics, wave phenomena, and mathematical physics. This discussion is beneficial for anyone looking to deepen their understanding of the de Broglie relation and its derivations.