FallenApple

- 564

- 61

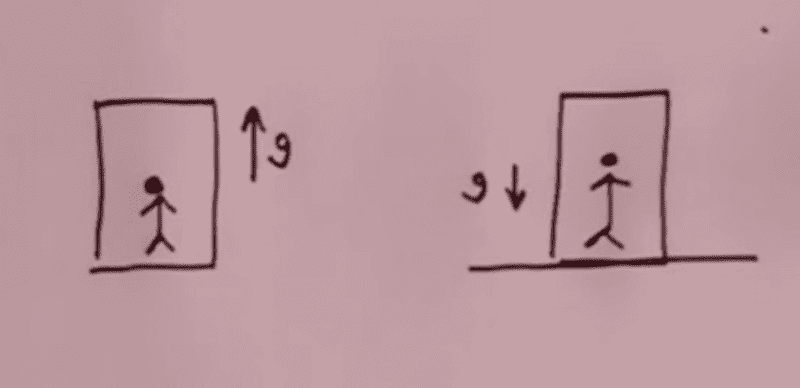

So if someone is in an elevator moving up at g in outer space, vs someone in an elevator in a uniform gravitational field of g, there is no way telling whether one is in an elevator in outer space or resting on earth.

But what is the big insight about this? Isn't this true classically as well?

I saw this clip where Brain Greene poked a few holes into a water bottle and dropped it, showing that in mid air, the water stops leaking, so the water is in free fall along with the bottle. But this "experiment" could have easily have been done in Newton's time. Surely Newton must have known. So where is the philosophical difference?

Is it because Einstein deduced that light must bend in an accelerating elevator? So the principle was already there, he just applied it in a novel way?

But what is the big insight about this? Isn't this true classically as well?

I saw this clip where Brain Greene poked a few holes into a water bottle and dropped it, showing that in mid air, the water stops leaking, so the water is in free fall along with the bottle. But this "experiment" could have easily have been done in Newton's time. Surely Newton must have known. So where is the philosophical difference?

Is it because Einstein deduced that light must bend in an accelerating elevator? So the principle was already there, he just applied it in a novel way?

Last edited: