rhody

Gold Member

- 679

- 3

Physics.org: March 10, 2010 By Lisa Zyga

comments go here

Hans-Otto Meyer, a physics professor at Indiana University has shown that the electron firings are distributed in time, in burst patterns, but in a "peculiar, correlated way", he believes the correlation involves some kind of trapping mechanism, not yet fully understood.

From the article,

and again later,

Meyer concludes:

Having looked at the band structure link posted above I realize why I belong to PF, this concept is best understood and explained by the physicist's who share and collaborate here.

Ideas as to the cause or causes of this phenomenon ?

Rhody...

comments go here

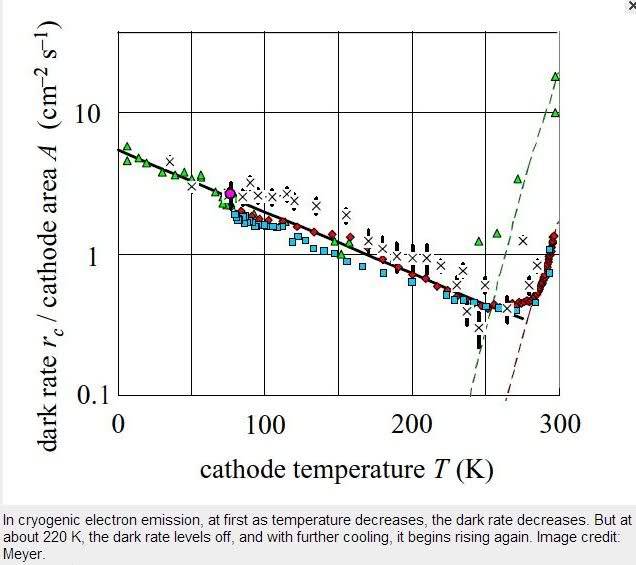

In cryogenic electron emission, at first as temperature decreases, the dark rate decreases. But at about 220 K, the dark rate levels off, and with further cooling, it begins rising again. Image credit: Meyer.

(PhysOrg.com) -- At very cold temperatures, in the absence of light, a photomultiplier will spontaneously emit single electrons. The phenomenon, which is called "cryogenic electron emission," was first observed nearly 50 years ago. Although scientists know of a few causes for electron emission without light (also called the dark rate) - including heat, an electric field, and ionizing radiation - none of these can account for cryogenic emission. Usually, physicists consider these dark electron events undesirable, since the purpose of a photomultiplier is to detect photons by producing respective electrons as a result of the photoelectric effect.

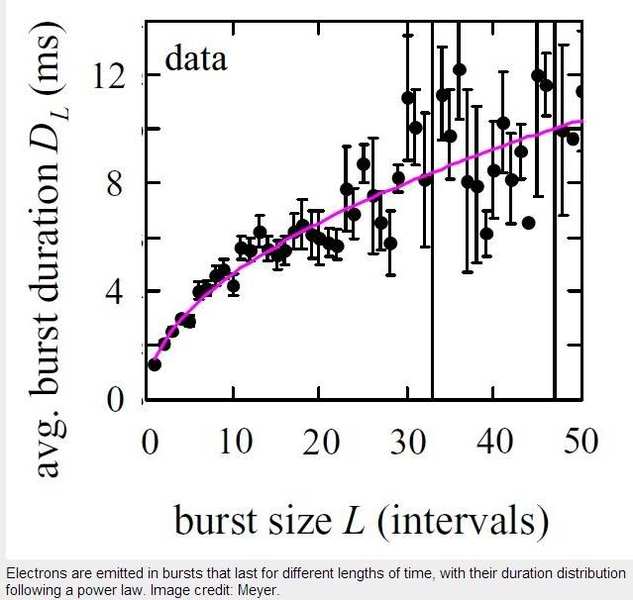

Hans-Otto Meyer, a physics professor at Indiana University has shown that the electron firings are distributed in time, in burst patterns, but in a "peculiar, correlated way", he believes the correlation involves some kind of trapping mechanism, not yet fully understood.

From the article,

Specifically, within a burst, events first occur rapidly, and then less and less frequently as the burst “fades away.”

and again later,

Among his interesting observations are that the cryogenic emission rate does not depend on whether the device is cooling or warming up, but only on the current temperature. Overall, the properties of cryogenic electron emission don’t fit with any other known spontaneous emission process, including thermal emission, field emission, radioactivity, or penetrating radiation such as cosmic rays.

Meyer concludes:

“Nature at very low temperatures has a lot of surprises up her sleeve,” Meyer said. “I don't want to speculate as to what will turn out to be the explanation of cryogenic emission, but I would not be surprised if the http://www.iue.tuwien.ac.at/phd/wessner/node31.html" plays an important role.”

Having looked at the band structure link posted above I realize why I belong to PF, this concept is best understood and explained by the physicist's who share and collaborate here.

Ideas as to the cause or causes of this phenomenon ?

Rhody...

Last edited by a moderator: