Nebuchadnezza

- 78

- 2

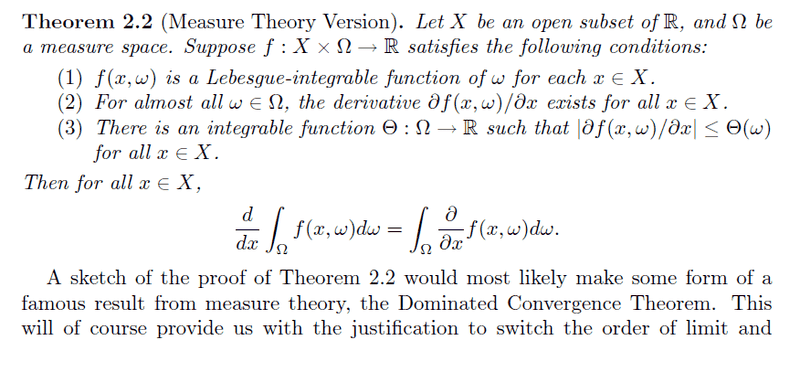

I am reading about Feynman integration or more commonly known as differentiating under the integral sign. My question is when can we use this method?

http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/mathematics/18-304-undergraduate-seminar-in-discrete-mathematics-spring-2006/projects/integratnfeynman.pdf

Here is a link explaining the method quite thoroughly. I have no problems actually performing the maths, I just don't know when I can apply this rule. I read the definition in the pdf, but since I have only taken Calc1 and some Calc2 this stumped me quite a bit. I am good at doing integration just not reading Greek... If anyone could explain this to me in layman terms, it would be much appreciated.

http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/mathematics/18-304-undergraduate-seminar-in-discrete-mathematics-spring-2006/projects/integratnfeynman.pdf

Here is a link explaining the method quite thoroughly. I have no problems actually performing the maths, I just don't know when I can apply this rule. I read the definition in the pdf, but since I have only taken Calc1 and some Calc2 this stumped me quite a bit. I am good at doing integration just not reading Greek... If anyone could explain this to me in layman terms, it would be much appreciated.

Last edited by a moderator: