This is simply the transformation between Lagrange and Euler descriptions of the fluid.

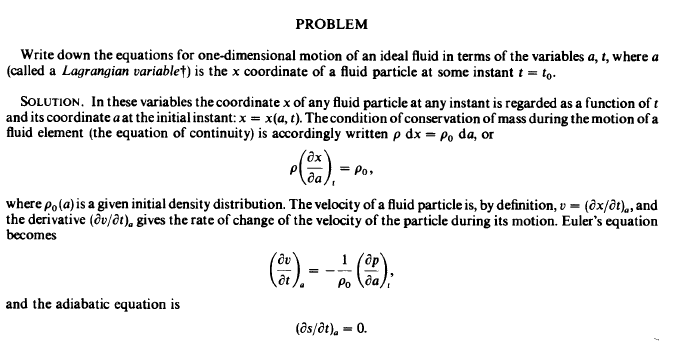

In the Lagrange description you use some standard configuration of a continuum mechanical system. For fluids you can choose the configuration at the initial time ##t##. Then one defines ##\vec{x}(t,\vec{y})## as the position of the fluid element at time ##t##, which has been located at ##\vec{y}## at time ##t=0##. We assume that the map ##\vec{y} \mapsto \vec{x}(t,\vec{y})## is smooth and invertible (a diffeomorphism).

Then the velocity of the fluid element is simply given by

$$\vec{v}_L(t,\vec{y})=\partial_t \vec{x}(t,\vec{y}).$$

That's the Lagrangian description of the fluid motion (and that's why I put an ##L## at the velocity).

The more familiar Eulerian description is found when thinking in terms of an observer looking at the fluid at position ##\vec{x}## and just describes the properties of the fluid element at time ##t## which is just at this position. Then you get the usual velocity field of fluid dynamics

$$\vec{v}(t,\vec{x})=\vec{v}_L[t,\vec{y}(t,\vec{x})],$$

where now we simply write ##\vec{y}(t,\vec{x})## for the inverse function of ##\vec{x}(t,\vec{y})##, i.e., ##\vec{y}(t,\vec{x})## gives the initial ##\vec{y}## of the fluid element which is at ##\vec{x}## at time ##t##.

From this you get the acceleration of a given fluid element as follows: In Lagrangian description it's simply

$$\vec{a}_L(t,\vec{y})=\partial_t \vec{v}_L(t,\vec{y}),$$

but now we want to express this in the Eulerian description. To that end we note that

$$\vec{v}_L(t,\vec{y})=\vec{v}[t,\vec{x}(t,\vec{y})].$$

And then we get

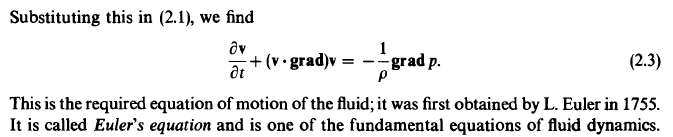

$$\vec{a}_L(t,\vec{y})=\vec{a}(t,\vec{x})=\partial_t \vec{v}[t,\vec{x}(t,\vec{y})]=\partial t \vec{v}(t,\vec{x}) + [\partial_t \vec{x}(t,\vec{y}) \cdot \vec{\nabla} \vec{v}(t,\vec{x}) = \partial_t \vec{v}(t,\vec{x}) + (\vec{v} \cdot\vec{\nabla}) \vec{v}(t,\vec{x}).$$

This you can generalized to the "substantial time derivative" of any quantity, and define

$$\mathrm{D}_t f(t,\vec{x})=\partial_t f(t,\vec{x}) + (\vec{v} \cdot \vec{\nabla}) f(t,\vec{x}).$$

Now again consider a fixed fluid element at the initial position ##\vec{y}##. Then the mass density in Lagrangian description is given by ##\rho_L(t,\vec{y})##.

Now for these given fluid particles the mass is conserved, i.e.,

$$\mathrm{d} m = \mathrm{d}^3 x \rho_L=\text{const}. \; \Rightarrow \; \partial_t \mathrm{d} m=0.$$

The partial time derivative has to be taken with ##\vec{y}## fixed.

In terms of the Eulerian density we have

$$\mathrm{d} m=\mathrm{d}^3 x \rho=\mathrm{d}^3 \vec{y} \mathrm{det} \frac{\partial \vec{x}}{\partial \vec{y}} \rho=\mathrm{d}^3 \vec{y} J(t,\vec{y}) \rho_L(t,\vec{y}).$$

Here ##J## is the Jacobian of the diffeomorphism ##\vec{y} \mapsto \vec{x}(t,\vec{y})##. The time derivative is given by

$$\partial_t J=(\vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{v}) J.$$

From this you get

$$\partial_t \mathrm{d}m =\mathrm{d}^3 y J (\partial_t \rho_L(t,\vec{y}) + \rho_L \vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{v}_L)=0.$$

Now we can rewrite this again in terms of the Eulerian description, using ##\partial_t \rho_L=\mathrm{D}_t \rho##:

$$\mathrm{D}_t \rho + \rho \vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{v}=0$$

or writing the material time derivative out

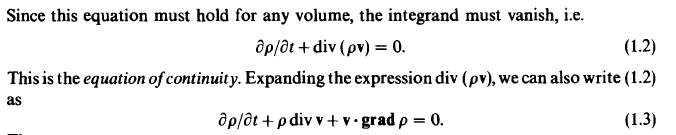

$$\partial_t \rho + (\vec{v} \cdot \vec{\nabla}) \rho + \rho \vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{v} = \partial_t \rho +\vec{\nabla} \cdot (\rho \vec{v})=0.$$

This is the equation of continuity for the mass,

$$\partial_t \rho + \vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{j},$$

where ##\vec{j}=\rho \vec{v}## is the mass-current density.

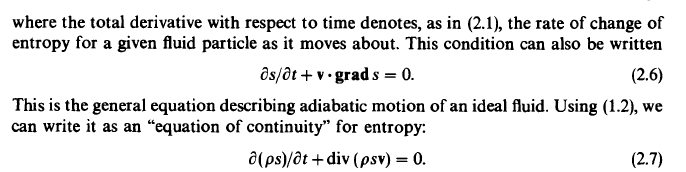

That the ideal fluid motion is adiabatic characterizes the ideal fluid which by definition does not dissipate energy into heat, i.e., the entropy per unit mass ##s## is constant for the corresponding fluid element, which means

$$\partial_t s_L(t,\vec{y})=\mathrm{D}_t s(t,\vec{x})=\partial_t s + (\vec{v} \cdot \vec{\nabla})s=0.$$

This only means that the entropy of each fluid element is conserved, indeed we have

$$\partial_t (\rho s) + \vec{\nabla} \cdot (\vec{j} s)=(\partial_t \rho + \vec{\nabla} \cdot \vec{j}) + \rho \partial_t s +(\vec{j} \cdot \vec{\nabla}) s=\rho (\partial_t s + \vec{v} \cdot \vec{\nabla} s)=0.$$

Where the equation of continuity is given earlier:

Where the equation of continuity is given earlier:

As is Euler's equation:

As is Euler's equation:

And the equation of continuity for entropy:

And the equation of continuity for entropy:

I don't understand how this conclusion was reached. I can understand the derivation for the equation of continuity , but I have no idea how you could derive it from Euler's equation:

I don't understand how this conclusion was reached. I can understand the derivation for the equation of continuity , but I have no idea how you could derive it from Euler's equation: