Sang Ho Lee

- 4

- 0

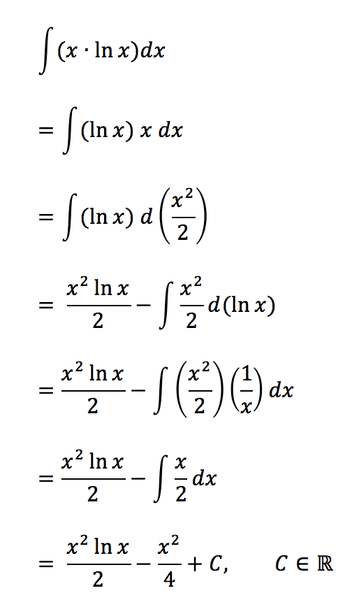

Hello, I'm currently taking calc 1 as an undergraduate student, and my professor just showed us a new? way of solving Integration By Parts.

This is the example he gave"

Is there a name for this technique that substitutes d(___) instead of dx?

Thank you,

This is the example he gave"

Is there a name for this technique that substitutes d(___) instead of dx?

Thank you,