qnach

- 154

- 4

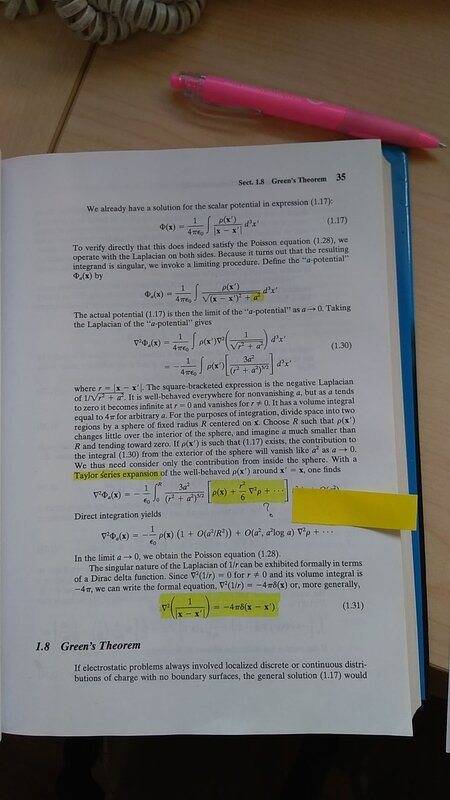

Could anyone explain how did Jackson obtain the Taylor distribution of charge distribution at the end of section 1.7 (version 3)?

The forum discussion focuses on the Taylor series expansion of charge distribution as presented in Jackson's "Classical Electrodynamics" (version 3). Participants analyze the second-order Taylor series expansion, specifically addressing the integration of first-order terms and the implications of spherical symmetry on the second-order terms. A key point of contention is the factor discrepancy in the Laplacian term, with contributors ultimately agreeing on a factor of 1/6 after detailed analysis. The discussion also clarifies the meaning of the big-O notation used in the context of the expansion.

PREREQUISITESPhysicists, graduate students in theoretical physics, and anyone studying classical electrodynamics who seeks a deeper understanding of charge distribution and mathematical techniques in field theory.

I think that's correct though I find the conclusion by Jackson a bit too quick, but after some detailed analysis, I think it's correct too.Charles Link said:The print isn't real clear, but I worked the next step. (The exponent in the denominator is ## \frac{5}{2} ##. It looks like ## \frac{3}{2} ##, but correctly it should be ## \frac{5}{2} ##).

## \int\limits_{0}^{+\infty} \frac{3 a^2 r^2}{(r^2+a^2)^{5/2}} \, dr ## can be readily solved by letting ## r=a \tan{\theta} ##.

To resolve the handwaving in post 2, ## \nabla^2 \rho =(\frac{\partial^2{\rho}}{\partial{x^2}}) + ## y and z second partial terms at ## \vec{x} ##, so that ## \nabla^2 \rho =3 (\frac{\partial^2{\rho}}{\partial{x^2}}) ## at ## \vec{x} ##. This ## \nabla^2 ## term is a constant when integrating over dr. It also is useful to look at the integrals of ## \int x^2 \, d^3 r ## vs. ## \int r^2 \, d^3 r ##, etc. Upon working through all the details, I agree with his ## \frac{1}{6} ##.

That's the Landauer big-O symbol. It tells you how in some limit of a variable a function behaves. In this case it's the limit ##a \rightarrow 0##, andqnach said:Could anyone please explain the meaning of the last term of the second last equation in this page.

What does O(a^2,a^2 log a) mean? The O notation contains only one term inside the bracket.

But this guy has two inside.