lys04

- 144

- 5

- Homework Statement

- constraints in Lagrange multiplier questions and the nature of the Extrema

- Relevant Equations

- ∇f= λ∇g

Here’s my basic understanding of Lagrange multiplier problems:

A typical Lagrange multiplier problem might be to maximise f(x,y)=x^2-y^2 with the constraint that x^2+y^2=1 which is a circle of radius 1 that lie on the x-y plane. The points on the circle are the points (x,y) that satisfy the constraint equation. The problem is to find which of these (x,y) points maximises the function f.

Can view x^2+y^2=1 as the level curve when c=1 for the function g(x,y)=x^2+y^2

And this might happen when the gradient of g is parallel to the gradient of f. This is because the gradient of f, a vector quantity, indicates the direction to move the (x,y) point to get the greatest rate of change of f. If this vector is perpendicular to the surface of the level curve, that means no component of the gradient vector is in the direction of the tangent line at the point (x,y). And because the gradient is perpendicular to the level curve at any point, this means the gradient of f is parallel to the gradient of g.

Here’s where I get confused,

Take the problem to be maximise f(x,y,z)=x^2-y^2+yz with the constraint z=y^2.

I know that I can rewrite the constraint equation into z-y^2=0, which can be viewed as the level curve c=0 of the function g(x,y,z)=z-y^2 or g(y,z)=z-y^2? I get a bit confused here but I believe the first one, g(x,y,z) is correct because only then the gradient will have 3 components and can be parallel to the gradient of f which also has 3 components?

So basically here I have the level SURFACE of g(x,y,z)=z-y^2 at c=0, and finding out which of these points on the level SURFACE gives me the maximum value of f?

And secondly, I would like to clarify Lagrange multiplier problems with two constraints.

Lagrange multiplier problems with two constraints, i.e maximising f with constraints g=c_1 and h=c_2 (assume that f, g and h are all functions of three variables). Then I want to find points (x,y,z) that satisfy both constraints, and out of these points I want to find ones that maximises/minimises f.

Given that the level curves of g and h intersect, call it C, along the curve, the gradients of g and h will be perpendicular to the tangent lines.

And when f is at a maximum/minimum, there is no direction I can move so that f will continue to increase/decrease. This means that the gradient of f at the maximum/minimum must be perpendicular to the tangent of C. This means that it’s also parallel to the gradients of g and h.

Using this equation below, I get 5 equations by taking the partial derivative with respect to each variable. (First image)

Here’s what I am confused about this, from the last 3 equations, how do we know that the gradient of f is parallel to that of g and h?

And I think it’s because:

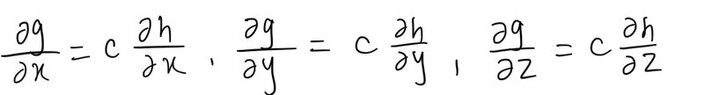

And since from before I know that the gradient of g and h are parallel, this means (second image)

So if I plug this into the equations above for the partial derivatives of x, y and z then I’ll get that the partial derivative of f with respect to x, y and z is equal to a scalar multiple times the partial derivative of h? (Not actually gonna do this, just an idea for how the partial derivative of f equally a linear combination of the partial derivatives of g and h means that they are parallel).

And I can’t use the second derivative test on the solutions I found to tell whether it’s a maximum or a minimum because these are not necessarily the critical points of f, although they are the critical points of L?

A typical Lagrange multiplier problem might be to maximise f(x,y)=x^2-y^2 with the constraint that x^2+y^2=1 which is a circle of radius 1 that lie on the x-y plane. The points on the circle are the points (x,y) that satisfy the constraint equation. The problem is to find which of these (x,y) points maximises the function f.

Can view x^2+y^2=1 as the level curve when c=1 for the function g(x,y)=x^2+y^2

And this might happen when the gradient of g is parallel to the gradient of f. This is because the gradient of f, a vector quantity, indicates the direction to move the (x,y) point to get the greatest rate of change of f. If this vector is perpendicular to the surface of the level curve, that means no component of the gradient vector is in the direction of the tangent line at the point (x,y). And because the gradient is perpendicular to the level curve at any point, this means the gradient of f is parallel to the gradient of g.

Here’s where I get confused,

Take the problem to be maximise f(x,y,z)=x^2-y^2+yz with the constraint z=y^2.

I know that I can rewrite the constraint equation into z-y^2=0, which can be viewed as the level curve c=0 of the function g(x,y,z)=z-y^2 or g(y,z)=z-y^2? I get a bit confused here but I believe the first one, g(x,y,z) is correct because only then the gradient will have 3 components and can be parallel to the gradient of f which also has 3 components?

So basically here I have the level SURFACE of g(x,y,z)=z-y^2 at c=0, and finding out which of these points on the level SURFACE gives me the maximum value of f?

And secondly, I would like to clarify Lagrange multiplier problems with two constraints.

Lagrange multiplier problems with two constraints, i.e maximising f with constraints g=c_1 and h=c_2 (assume that f, g and h are all functions of three variables). Then I want to find points (x,y,z) that satisfy both constraints, and out of these points I want to find ones that maximises/minimises f.

Given that the level curves of g and h intersect, call it C, along the curve, the gradients of g and h will be perpendicular to the tangent lines.

And when f is at a maximum/minimum, there is no direction I can move so that f will continue to increase/decrease. This means that the gradient of f at the maximum/minimum must be perpendicular to the tangent of C. This means that it’s also parallel to the gradients of g and h.

Using this equation below, I get 5 equations by taking the partial derivative with respect to each variable. (First image)

Here’s what I am confused about this, from the last 3 equations, how do we know that the gradient of f is parallel to that of g and h?

And I think it’s because:

And since from before I know that the gradient of g and h are parallel, this means (second image)

So if I plug this into the equations above for the partial derivatives of x, y and z then I’ll get that the partial derivative of f with respect to x, y and z is equal to a scalar multiple times the partial derivative of h? (Not actually gonna do this, just an idea for how the partial derivative of f equally a linear combination of the partial derivatives of g and h means that they are parallel).

And I can’t use the second derivative test on the solutions I found to tell whether it’s a maximum or a minimum because these are not necessarily the critical points of f, although they are the critical points of L?