zhuang382

- 9

- 2

Let ##K## and ##K'## be two inertial frame, If K is moving with infinitesimal velocity relative to ##K'## , then ##v' = v + \epsilon##.

Note that ##L(v^2) - L(v'^2)## is only a total derivative of a function of coordinate and time. (I understand this part)

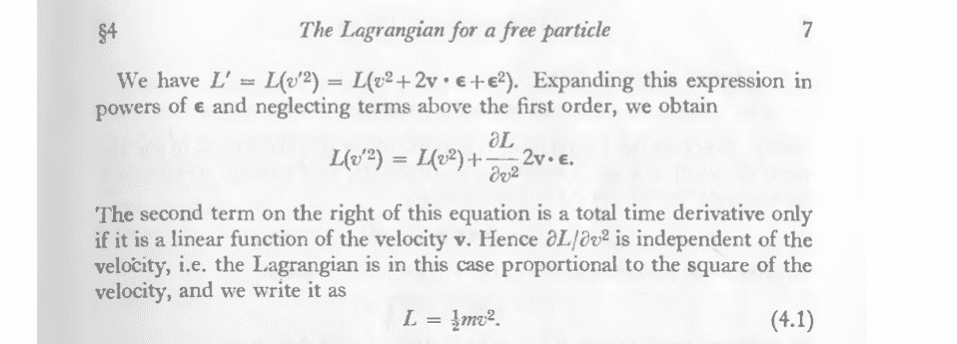

Because ##L' = L(v'^2) = L(v^2 + 2v\cdot\epsilon + \epsilon^2)##, then we use power series of ##\epsilon## to expand the equation and neglect the second order term:

$$L(v'^2) = L(v^2) + 2\frac {\partial f} {\partial v^2}v\cdot\epsilon$$

Then the author argues that it is only when the second term on the right hand side is a linear function of ##\vec{v}##, it is a total derivative of time; therefore ##\frac{\partial f} {\partial v^2}## does not depend on velocity. Can someone help me on the detail of ##\epsilon## series expansion and how the conclusion drawn from this?

Note that ##L(v^2) - L(v'^2)## is only a total derivative of a function of coordinate and time. (I understand this part)

Because ##L' = L(v'^2) = L(v^2 + 2v\cdot\epsilon + \epsilon^2)##, then we use power series of ##\epsilon## to expand the equation and neglect the second order term:

$$L(v'^2) = L(v^2) + 2\frac {\partial f} {\partial v^2}v\cdot\epsilon$$

Then the author argues that it is only when the second term on the right hand side is a linear function of ##\vec{v}##, it is a total derivative of time; therefore ##\frac{\partial f} {\partial v^2}## does not depend on velocity. Can someone help me on the detail of ##\epsilon## series expansion and how the conclusion drawn from this?