Apashanka

- 427

- 15

Again in pg. 166 eq 7.2

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&sou...FjACegQIBhAB&usg=AOvVaw1YY2mM7uccdbX4nTxFgQO5

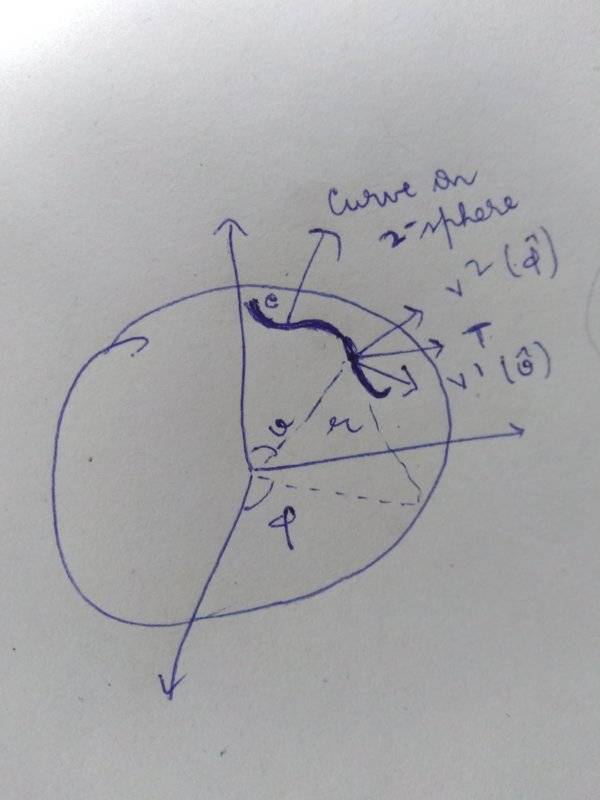

Here ##u^1=\theta,u^2=\phi## and v=r.

The tangent vector on the sub-manifold points on ##V^1 \hat \theta## & ##V^2 \hat \phi##.

It is written here to get rid of cross terms the tangent vectors##\frac{∂}{∂V^I}## (here ##\frac{∂}{∂r}##) is made perpendicular to the submanifolds.

Can anyone please explain what is the last line trying to say and how it will be applicable here??

https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&sou...FjACegQIBhAB&usg=AOvVaw1YY2mM7uccdbX4nTxFgQO5

Here ##u^1=\theta,u^2=\phi## and v=r.

The tangent vector on the sub-manifold points on ##V^1 \hat \theta## & ##V^2 \hat \phi##.

It is written here to get rid of cross terms the tangent vectors##\frac{∂}{∂V^I}## (here ##\frac{∂}{∂r}##) is made perpendicular to the submanifolds.

Can anyone please explain what is the last line trying to say and how it will be applicable here??