mathmari

Gold Member

MHB

- 4,984

- 7

Hey!

I am looking at the divide-and-conquer technique for the multiplication of two $n-$bit numbers.First of all, why does the traditional method of the multiplication of two $n-$bit numbers require $O(n^2)$ bit operations?? (Wondering)

The divide-and-conquer approach is the following:

Let $x$ and $y$ be two $n-$bit numbers. (For simplicity we assume that $n$ is a power of $2$.)

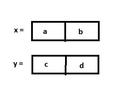

We partition $x$ and $y$ into two halves as followed:

View attachment 3595

If we treat each half as an $(n/2)-$bit number, then we can express the product as follows:

$$xy=(a2^{n/2}+b)(c2^{n/2}+d)=ac2^n+(ad+bc)2^{n/2}+bd \ \ \ \ \ (*)$$

Equation $(*)$ computes the product of $x$ and $y$ by four multiplications of $(n/2)-$bit numbers plus some additions and shifts (multiplications by powers of $2$).

Could you explain me the partition of $x$ and $y$?? (Wondering)

Also, why do we write the product as in $(*)$ ?? (Wondering)

I am looking at the divide-and-conquer technique for the multiplication of two $n-$bit numbers.First of all, why does the traditional method of the multiplication of two $n-$bit numbers require $O(n^2)$ bit operations?? (Wondering)

The divide-and-conquer approach is the following:

Let $x$ and $y$ be two $n-$bit numbers. (For simplicity we assume that $n$ is a power of $2$.)

We partition $x$ and $y$ into two halves as followed:

View attachment 3595

If we treat each half as an $(n/2)-$bit number, then we can express the product as follows:

$$xy=(a2^{n/2}+b)(c2^{n/2}+d)=ac2^n+(ad+bc)2^{n/2}+bd \ \ \ \ \ (*)$$

Equation $(*)$ computes the product of $x$ and $y$ by four multiplications of $(n/2)-$bit numbers plus some additions and shifts (multiplications by powers of $2$).

Could you explain me the partition of $x$ and $y$?? (Wondering)

Also, why do we write the product as in $(*)$ ?? (Wondering)