Happiness

- 686

- 30

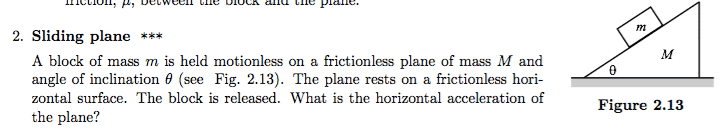

For the following question, how do we know that the acceleration of ##M## is constant over time? And is the normal contact force between the two masses smaller as compared to that where ##M## is fixed?

The acceleration depends on the net force on ##M##, which depends on the normal contact force ##N## between ##m## and ##M##. The force ##N## depends on how tightly the two surfaces are pressed together. So it seems plausible that ##N## is smaller when ##M## is free to slide compared to that when ##M## is fixed.

The initial velocities of ##m## and ##M## are zero. Suppose we set up the initial conditions by holding ##m## and ##M## fixed and then release them. Would the initial (when both masses are just released from grip) value of ##N## in this case be the same as the value of ##N## where ##M## is always fixed?

I guess they would be the same. But since the acceleration is constant over time, the value of ##N##, at all other time after ##M## starts to slide, must be the same as the initial value of ##N##. Then, we must conclude that the value of ##N## where ##M## is fixed is equal to the value of ##N## where ##M## is sliding away from ##m##. But when ##M## is sliding, it seems that the two masses are less tightly pressed together, and so ##N## should be smaller.

The acceleration depends on the net force on ##M##, which depends on the normal contact force ##N## between ##m## and ##M##. The force ##N## depends on how tightly the two surfaces are pressed together. So it seems plausible that ##N## is smaller when ##M## is free to slide compared to that when ##M## is fixed.

The initial velocities of ##m## and ##M## are zero. Suppose we set up the initial conditions by holding ##m## and ##M## fixed and then release them. Would the initial (when both masses are just released from grip) value of ##N## in this case be the same as the value of ##N## where ##M## is always fixed?

I guess they would be the same. But since the acceleration is constant over time, the value of ##N##, at all other time after ##M## starts to slide, must be the same as the initial value of ##N##. Then, we must conclude that the value of ##N## where ##M## is fixed is equal to the value of ##N## where ##M## is sliding away from ##m##. But when ##M## is sliding, it seems that the two masses are less tightly pressed together, and so ##N## should be smaller.

Last edited: