e4c6

- 3

- 2

- Homework Statement

- Proof of Schrodinger equation solution persisting in time

- Relevant Equations

- Schrodinger equation

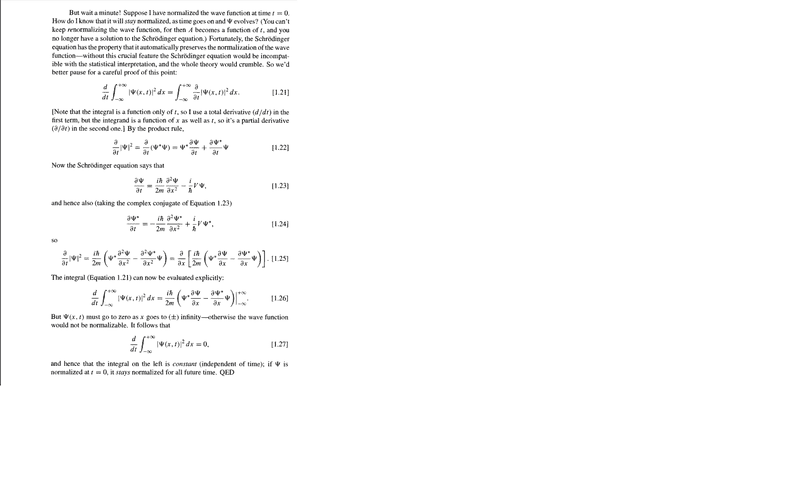

I've started reading Introduction to Quantum Mechanics by Griffiths and I encountered this proof that once normalized the solution of Schrödinger equation will always be normalized in future:

And I am not 100% convinced to this proof. In 1.26 he states that ##\Psi^{*} \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial x} - \Psi \frac{\partial \Psi^{*}}{\partial x}## must go to 0 at infinity as ##\Psi## must vanish in infinity(I've also found very similar reasoning in some youtube video but nothing more precise). However ##\Psi## vanishing in the infinity doesn't imply that its derivative also goes to 0. For example consider:

$$\Psi = \frac{sin(x^3)}{x} - \frac{i}{x}$$

Then:

$$\Psi^{*} \Psi = \left(\frac{sin(x^3)}{x}\right)^2 + \frac{1}{x^2}$$

So integral of probability is finite and then:

$$\Psi^{*} \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial x} - \Psi \frac{\partial \Psi^{*}}{\partial x} = 6icos(x^3)$$

Which doesn't equal 0. I've only written x - dependent part of the wave function but we can add some constants and time dependent part to get a proper(I think) solution which is a counterexample. What's wrong with my reasoning?

And I am not 100% convinced to this proof. In 1.26 he states that ##\Psi^{*} \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial x} - \Psi \frac{\partial \Psi^{*}}{\partial x}## must go to 0 at infinity as ##\Psi## must vanish in infinity(I've also found very similar reasoning in some youtube video but nothing more precise). However ##\Psi## vanishing in the infinity doesn't imply that its derivative also goes to 0. For example consider:

$$\Psi = \frac{sin(x^3)}{x} - \frac{i}{x}$$

Then:

$$\Psi^{*} \Psi = \left(\frac{sin(x^3)}{x}\right)^2 + \frac{1}{x^2}$$

So integral of probability is finite and then:

$$\Psi^{*} \frac{\partial \Psi}{\partial x} - \Psi \frac{\partial \Psi^{*}}{\partial x} = 6icos(x^3)$$

Which doesn't equal 0. I've only written x - dependent part of the wave function but we can add some constants and time dependent part to get a proper(I think) solution which is a counterexample. What's wrong with my reasoning?