member 731016

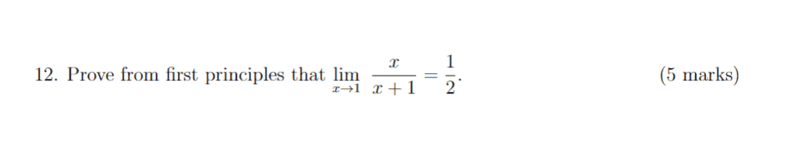

- Homework Statement

- Please see below

- Relevant Equations

- Please see below

For this problem,

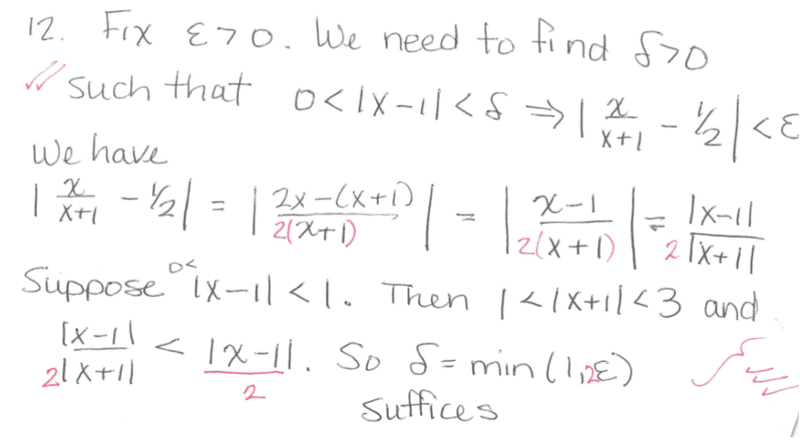

The solution is,

However, I'm confused how ##0 < | x - 1|< 1## (Putting a bound on ##| x- 1|##) implies that ##1 < |x+1| < 3##. Does someone please know how?

My proof is,

##0 < | x - 1|< 1##

##|2| < | x - 1| + |2| < |2| + 1##

##2 < |x - 1| + |2| < 3##

Then take absolute values of all three sides of the equation,

##|2| < ||x - 1| + |2|| < |3|##

This allows us to remove the absolute values around the x - 1 and 2. Thus,

##|2| < |x - 1 + 2| < |3|##

##|2| < |x + 1| < |3|##

##2 < |x + 1| < 3##

However, the two on the LHS side is wrong.

Thanks!

The solution is,

However, I'm confused how ##0 < | x - 1|< 1## (Putting a bound on ##| x- 1|##) implies that ##1 < |x+1| < 3##. Does someone please know how?

My proof is,

##0 < | x - 1|< 1##

##|2| < | x - 1| + |2| < |2| + 1##

##2 < |x - 1| + |2| < 3##

Then take absolute values of all three sides of the equation,

##|2| < ||x - 1| + |2|| < |3|##

This allows us to remove the absolute values around the x - 1 and 2. Thus,

##|2| < |x - 1 + 2| < |3|##

##|2| < |x + 1| < |3|##

##2 < |x + 1| < 3##

However, the two on the LHS side is wrong.

Thanks!