JimJCW

Gold Member

- 208

- 40

- TL;DR

- Let’s plot the temperature of the universe as a function of the cosmological time based on the ΛCDM Model and discuss the results.

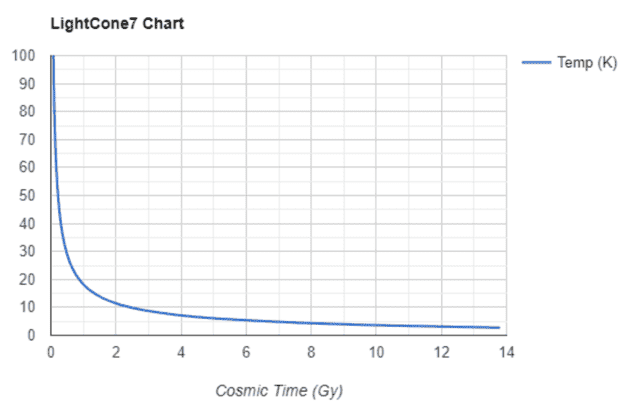

Using Jorrie’s calculator we can get the following T vs. t graph up to z = 20,000:

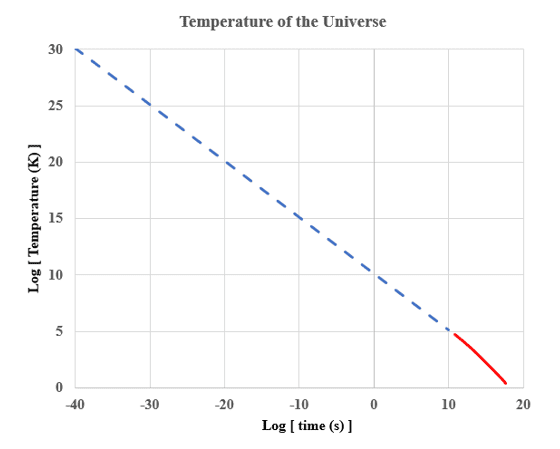

In a log-log plot the above curve is represented by the red solid line in the figure shown below:

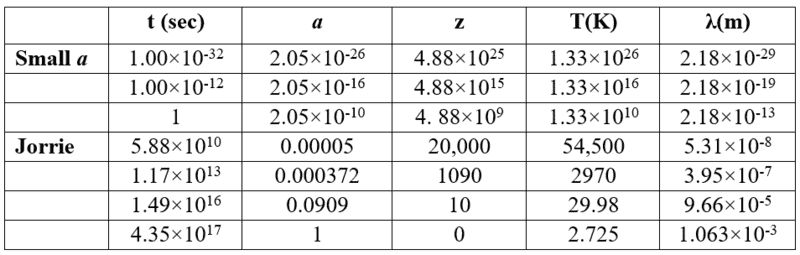

The dashed line shows results for the small a limit using the equation T = 2.725 K / a. Here are some tabulated numbers associated with the above plot:

The values of λ are calculated with the equation λ = 1.063 mm × a, based on the peak wavelength of the CMB at the present time.

Note that the above results are qualitatively consistent with the Tabular summary included in the Wikipedia webpage titled Chronology of the universe. According to the estimates in the summary, for t = 1E-12 s, T = 1E15 K and for t = 1 s, T = 1E10 K.

You can help by examining and commenting on the approach given here and see whether it makes sense.

In a log-log plot the above curve is represented by the red solid line in the figure shown below:

The dashed line shows results for the small a limit using the equation T = 2.725 K / a. Here are some tabulated numbers associated with the above plot:

The values of λ are calculated with the equation λ = 1.063 mm × a, based on the peak wavelength of the CMB at the present time.

Note that the above results are qualitatively consistent with the Tabular summary included in the Wikipedia webpage titled Chronology of the universe. According to the estimates in the summary, for t = 1E-12 s, T = 1E15 K and for t = 1 s, T = 1E10 K.

You can help by examining and commenting on the approach given here and see whether it makes sense.