- #1

MattRob

- 211

- 29

- TL;DR Summary

- Re-writing the simple exponential scale height model of atmospheric pressure to apply within a rotating cylinder in a co-rotating frame of reference, accounting for gravity (centrifugal force) and infinitesimal element volume being functions of radius.

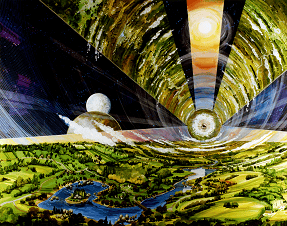

So, first off, for the uninitiated, an O'Neil Cylinder is a megastructure meant to be a space colony for humanity to live in in an Earth-like "outdoor" environment free-floating in space (ie, not on the surface of any celestial body with any significant gravity). It is essentially a cylinder that rotates about its Z-axis (for cylindrical coordinates θ, r, z) in order to provide artificial gravity on the inner surface. It is also pressurized with an Earth-like atmospheric mix of gasses to simulate an outdoor Earth-like environment on that cylinder's inner surface (and of course all the other life support functions necessary to do so).

You can read more about Gerard K. O'Neil's original designs here, it's a great read.

(Image credits: First image (painting), second image (CG - VRChat), third image (painting-style, from "Mobile Gundam"))

Recently I've started a long endeavor to design one of these out in more explicit detail and render it with realistic graphics, and one aspect I've wondered about for some years now is visibility. Just how much would various parts of it be obscured by atmospheric scattering? And how low would the air pressure be along the center axis? Could an airplane fly up there? While the visible light scattering involves other factors, before I can start on those I need a good model of air pressure vs altitude.

All that to say, a "simple" exponential "scale height" model is sufficiently precise for my purposes here. And to that end, I'll use "density" and "pressure" almost interchangeably sometimes, since we'll assume a constant gas mix and temperature, so pressure and density will be related by a simple proportionality constant ##P(r) = α ρ(r)## where ##α = RT/M## where ##R## is the gas constant, ##T## is temperature of the gas in Kelvin, and ##M## is the mean mass of one mol of the gaseous particles. (##M = 0.029 ~\rm{kg/mol}## for Earth).

So, first, I simply followed the derivation on the wikipedia page for Scale Height, but found a function ##g(r)## to substitute the constant ##g## with.

Addendum: These next sections are mostly included for completeness in case one of them was right, or I just barely missed in one particular step. But, after writing this post, I'm realizing I may have stumbled on the solution while writing it - see the last section titled "Equation 3?" - though that is a modification to eq. 0, which I derived in this next section:

In the context it was originally made for, ##z = 0## wais a point on Earth's surface and increasing ##z## denotes an increase in altitude, so I'll make ##z = 0## correspond to ##r = R_0## where ##R_0## is the radius of the cylinder, and so ##z = R_0## then corresponds to ##r = 0## (not to be confused with the cylindrical coordinate ##z## - no reference is being made to that cylindrical ##z##-coordinate in this section, so assume any ##z## here is the Cartesian system the base scale height equation was originally written in). So then we have $$z = R_0 - r$$ $$dz = -dr$$ And finally, just to make things a bit cleaner, I'll introduce ##H_0 = gH = \frac{k_B T}{m}## (and since we have the same gas mix and temperature as Earth, ##H_0 = g_⊕ H_⊕## Substituting that into the equation from the wikipedia page, $$\frac{dP}{P} = \frac{-dz}{\frac{k_B T}{m g}} = \frac{m g dr}{k_B T} = \frac{g(r) dr}{H_0} =$$ $$\frac{dP}{P} = \frac{4π^{2}}{T^{2} H_0} r dr$$ From here, I'll simply say it's not to difficult to get what I finally wound up with after integrating both sides and solving and setting a coefficient such that ##P(R_0) = P_0##,

$$P(r) = P_0 e^{\kappa (r^2 - R_0^2)}$$

(eq. 0)

where ##\kappa = \frac{2 π^{2}} {H_0 T^2} = \frac{2 π^{2}} {g_⊕ H_⊕ T^2}## and ##T = 2π \sqrt{\frac{R_0}{g_⊕}}## (ie, the cylinder rotates with a period such that the artificial gravity in the co-rotating frame on the inner surface (##r ≈ R_0##) is equal to Earth gravity ##g_⊕##), so ##\kappa## can be further reduced to: ##\kappa = \frac{1}{2 H_⊕ R_0}##.

That looks nice and clean and it works out in Desmos, and I was quite happy with it for awhile... HOWEVER,

To be even more explicit, as we integrate infinitesimal elements ##dr##, the volume is a tube of radius ##r## and thickness ##dr##, such that on the x,y (or equivalently, θ, r) plane, its area is ##A = π(r + \frac{1}{2} dr)^2 - π(r - \frac{1}{2} dr)^2## swept along the z-axis a distance ##dz##, such that $$dV = 2π r dr dz$$ - it has ##r##-dependence.

Furthermore, while in the Carteasian case, the area on the bottom of an infinitesimal cube is ##dA = dxdy##, in this cylindrical case, it's the perimeter of a circle of radius ##r + \frac{1}{2}dr## swept a distance along the z-axis ##dz##, such that ##dA = 2π(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)dz##

So I tried working it from a more basic level. I tried this process with constant ##g##, ##dV = dxdydz##, and ##dA = dxdy## and successfully re-derived the classic ##P(z) = P_0 e^{\frac{-z}{H}}## equation, so I think these steps should work for our case? At any rate, here are the steps in question:

The infinitesimal change in pressure ##dP## for an infinitesimal change in radius ##dr## should be as follows:

$$dP = \frac{dF}{dA} = \frac{dV ρ g(r)}{dA} = \frac{2π r dr dz}{2π(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)dz} ρ g(r) = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} ρ g(r)$$

Now, same as in the previous section, ##g(r) = \frac{4π^2}{T^2} r##, and using this from the wiki (which I've checked just comes straight from the ideal gas law): ##ρ = \frac{MP}{RT}##, and using my old ##H_0 = \frac{RT}{M} = g_⊕ H_⊕## (since same gas mix and temperature as Earth), so ##ρ = \frac{P}{H_0}##, so

$$dP = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} ρ g(r) = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} \frac{P}{H_0} \frac{4π^2}{T^2} r $$

Introducing another constant to clean things up a bit, a new kappa, similar to the old one in the previous section: ##\kappa = \frac{4π^2}{T^2 H_0}##,

$$dP = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} \frac{P}{H_0} \frac{4π^2}{T^2} r = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} P \kappa r = \kappa \frac{r^2 dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} P ⇒ \frac{dP}{\kappa P} = \frac{r^2 dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)}$$ I really don't know how I'm supposed to integrate that. So re-arranging to try to split up the fraction on the RHS so I can get all the differentials out of the denominators,

$$\frac{dP}{\kappa P} = \frac{r^2 dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} ⇒ \frac{\kappa P}{dP} = \frac{r + \frac{1}{2}dr}{r^2 dr} = \frac{1}{rdr} + \frac{1}{2r^2}$$

$$⇒2 \kappa rdr - 2 \frac{1}{P} dP = \frac{1}{rP} dr dP$$ and I'm not even sure how to go from here with this nonlinear term. Interestingly it changes by the same form whether I choose to integrate it by ##dr## or ##dP##:

$$2 \kappa \int rdr - 2 \int \frac{1}{P} dP = \int \frac{1}{rP} dr dP$$

$$= \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P) = ln(r) \frac{1}{P} dP$$ or is it?... $$= \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P) = ln(P) \frac{1}{r} dr$$ If both are valid, then, since I don't know what else to do with equations of this form with a single differential (how am I supposed to integrate both sides if there's only something to integrate one side with respect to? An integrand without a differential is meaningless, isn't it?), I decided to try a numerical approach, so solved for the differentials: $$dP = \frac{P}{ln(r)} ( \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P))$$ $$dr = \frac{r}{ln(P)} ( \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P))$$

(eq. set 1)

Which is a bit troubling since last night I got

$$dr = \frac{r}{P} ( \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P))$$

$$dP = \frac{1}{ln(r)} ( \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P))$$

(eq. set 2)

I really don't feel like I know what I'm doing, but I do understand many differential equations have to be solved numerically, so I took a crack at it with a little C# script. I simply start with an initial ##r## and ##P## (with all the natural logs, using units of atmospheres for ##P## didn't go well (which isn't a great sign), so I decided to try using pascals, so my initial values were ##r = 24,000 ~\rm{meters}## and ##P = 101,325 ~\rm{Pa}##.

As for the constants, recall ##\kappa = \frac{4π^2}{T^2 H_0}##, setting the rotation period ##T## such that there's earth-surface gravity on the inner surface ##g_⊕ ≈ 9.81## and the radius of the cylinder is ##R_0 = 24,000 ~\rm{meters}##, and going back to basic kinematics again, ##a = \frac{v^2}{r} = g_⊕ = \frac{v^2}{R_0}## (for artificial gravity in our co-rotating frame), and ##v = \frac{dx}{dt} = \frac{2πR_0}{T}## to get ##g_⊕ = \frac{4π^2 R_0}{T^2}##, and solving to get ##T = 2π \sqrt{\frac{R_0}{g_⊕}}##. So ##\kappa = \frac{4π^2}{T^2 H_0} = \frac{1}{\frac{R_0}{g_⊕} H_0}##, and recalling that ##H_0 = \frac{RT}{M} = g_⊕ H_⊕##, we plug that in to finally get $$\kappa = \frac{1}{R_0 H_⊕}$$

And ##H_⊕ ≈ 8,500 ~\rm{meters}##.

So, to get these curves, I had my script iterate by working off an initial ##P##, ##r## and solving eq. set 1 or 2 for ##dr## and ##dP##, then using those to advance one step, a bit like this:

though of course there's a lot more code to it than that, that's the core part of how it functions. I know there are far better methods like Runge-Kutta and others, and this is something like Euler's that I'm using, but I don't need much precision for this application, just something easy and quick to write, I think this is probably good enough, given I can easily run tens of thousands of steps.

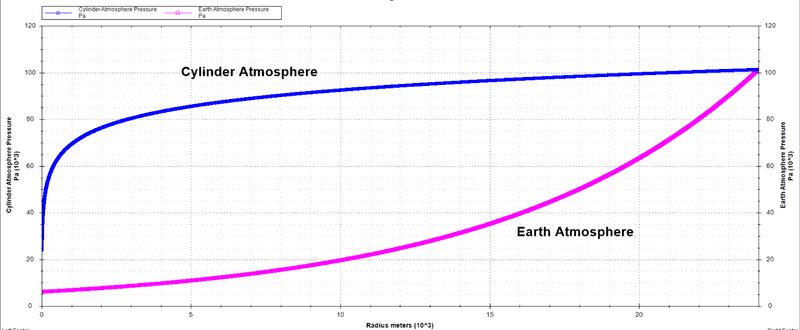

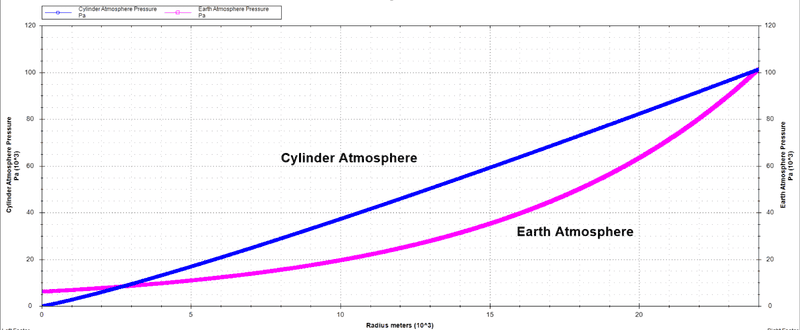

Altogether, though, when I ran the numerical integration, the curve I got using eq. set 2 did not look physical:

(Earth atmosphere included for reference in pink)

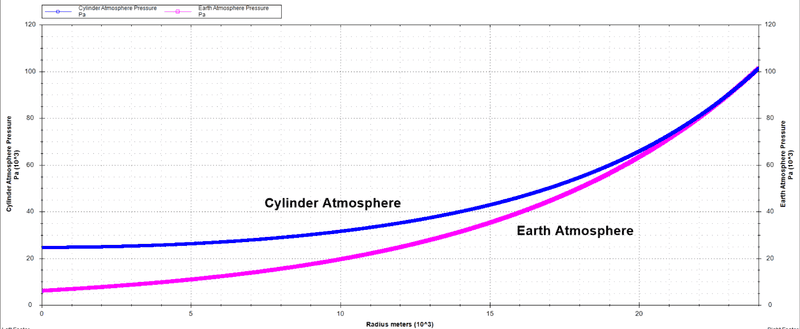

And using eq. set 1:

Doing some more work on eq. set 1, I've come to realize I'm pretty sure that "symmetry" I noticed actually proves that ##\frac{dP}{dr} = 1##, so it's literally just a linear slope, with perhaps a bit of a curve because of my numerical methods being very basic.

To be honest, both of those look less physical to me than the first equation, which didn't take into account the fact that there's less air resting on top of each air element due to the circumference shrinking as you approach the cylinder's z-axis:

Because, after all, while the air pressure should drop as you go towards the middle of the cylinder, it shouldn't go to zero. While modelling an atmosphere on a planet seems to work fine with modelling all the pressure as resulting from the weight of air above, with a rotating cylinder where the gravity goes to zero in a finite distance, that method seems to fail since the zero gravity at the Z-axis would imply zero weight, therefore no pressure.

But that's obviously not right, a pressurized cylinder in space won't somehow lose all its pressure just because there's no gravity.

But at the same time, eq. 0 doesn't take into account the fact that there's more than twice as much air resting on top of an element of air at ##r = 2## than at ##r = 1## since the volume increases with the square of the radius rather than linearly as it does in the base scale height model with an increase in ##z##.

On that note, that's just another power ##r## by which the curve should change. So could it be as simple as raising the exponent and then re-normalizing so that ##P(R_0) = P_0## like so?

$$P(r) = P_0 e^{\kappa (r^2 - R_0^2)}$$ $$→ P(r) = P_0 e^{\frac{\kappa}{R_0} (|r^3| - R_0^3)}$$ and let's get rid of the kappa, since it doesn't seem to be simplifying it as much as it was earlier: $$P(r) = P_0 e^{\frac{1}{2H_⊕ R_0^2} (|r^3| - R_0^3)}$$

(It may seem alarming that there's no visible dependence on the rotation rate of the cylinder, but in our derivation we defined the rotation rate such that the artificial gravity on the inner surface was the same as Earth gravity, and thus we had an extra ##g_⊕## to cancel out the##g_⊕## in ##H_0 = H_⊕ g_⊕##. So if we wanted to add that dependence back in, it would be

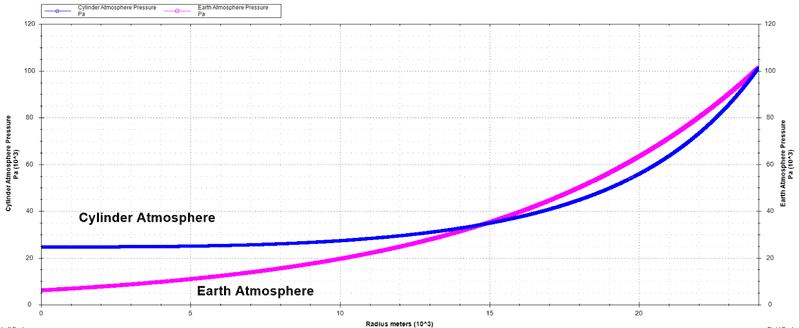

Trying that in the numerical code, it works... disturbingly well, at least to my intuition:

That would be some great cosmic humor if it really was that simple all along...

Anyways, any help or feedback on this would be greatly appreciated. I really ought to be more familiar with working with differentials in odd problems like this.

You can read more about Gerard K. O'Neil's original designs here, it's a great read.

(Image credits: First image (painting), second image (CG - VRChat), third image (painting-style, from "Mobile Gundam"))

Recently I've started a long endeavor to design one of these out in more explicit detail and render it with realistic graphics, and one aspect I've wondered about for some years now is visibility. Just how much would various parts of it be obscured by atmospheric scattering? And how low would the air pressure be along the center axis? Could an airplane fly up there? While the visible light scattering involves other factors, before I can start on those I need a good model of air pressure vs altitude.

All that to say, a "simple" exponential "scale height" model is sufficiently precise for my purposes here. And to that end, I'll use "density" and "pressure" almost interchangeably sometimes, since we'll assume a constant gas mix and temperature, so pressure and density will be related by a simple proportionality constant ##P(r) = α ρ(r)## where ##α = RT/M## where ##R## is the gas constant, ##T## is temperature of the gas in Kelvin, and ##M## is the mean mass of one mol of the gaseous particles. (##M = 0.029 ~\rm{kg/mol}## for Earth).

So, first, I simply followed the derivation on the wikipedia page for Scale Height, but found a function ##g(r)## to substitute the constant ##g## with.

Addendum: These next sections are mostly included for completeness in case one of them was right, or I just barely missed in one particular step. But, after writing this post, I'm realizing I may have stumbled on the solution while writing it - see the last section titled "Equation 3?" - though that is a modification to eq. 0, which I derived in this next section:

Variable g:

From kinematics, centrifugal acceleration (which is our "gravity" in our co-rotating frame), $$a = \frac{v^2}{r} = g(r),$$ and going back to basics, $$v = \frac{Δx}{Δt} = \frac{2πr}{T}$$ where ##T## is the period of one rotation, and substituting that back in to ##g(r)##, $$g(r) = \frac{4π^2}{T^2} r$$ But before I can use that, I need to transform ##z## into ##r##, so I simply imagine Wikipedia's ##z## is the ##x## or ##y## coordinate of a Cartesian coordinate system whose origin is shifted along either the ##x## or ##y## axis by ##R_0##, and is also co-rotating with my cylindrical coordinate system, but whose origin is fixed with respect to the cylindrical coordinate system.In the context it was originally made for, ##z = 0## wais a point on Earth's surface and increasing ##z## denotes an increase in altitude, so I'll make ##z = 0## correspond to ##r = R_0## where ##R_0## is the radius of the cylinder, and so ##z = R_0## then corresponds to ##r = 0## (not to be confused with the cylindrical coordinate ##z## - no reference is being made to that cylindrical ##z##-coordinate in this section, so assume any ##z## here is the Cartesian system the base scale height equation was originally written in). So then we have $$z = R_0 - r$$ $$dz = -dr$$ And finally, just to make things a bit cleaner, I'll introduce ##H_0 = gH = \frac{k_B T}{m}## (and since we have the same gas mix and temperature as Earth, ##H_0 = g_⊕ H_⊕## Substituting that into the equation from the wikipedia page, $$\frac{dP}{P} = \frac{-dz}{\frac{k_B T}{m g}} = \frac{m g dr}{k_B T} = \frac{g(r) dr}{H_0} =$$ $$\frac{dP}{P} = \frac{4π^{2}}{T^{2} H_0} r dr$$ From here, I'll simply say it's not to difficult to get what I finally wound up with after integrating both sides and solving and setting a coefficient such that ##P(R_0) = P_0##,

$$P(r) = P_0 e^{\kappa (r^2 - R_0^2)}$$

(eq. 0)

where ##\kappa = \frac{2 π^{2}} {H_0 T^2} = \frac{2 π^{2}} {g_⊕ H_⊕ T^2}## and ##T = 2π \sqrt{\frac{R_0}{g_⊕}}## (ie, the cylinder rotates with a period such that the artificial gravity in the co-rotating frame on the inner surface (##r ≈ R_0##) is equal to Earth gravity ##g_⊕##), so ##\kappa## can be further reduced to: ##\kappa = \frac{1}{2 H_⊕ R_0}##.

That looks nice and clean and it works out in Desmos, and I was quite happy with it for awhile... HOWEVER,

Cylindrical geometry:

I'm pretty sure the whole "Variable g" section above is wrong, because it's built on this previous line: $$\frac{dP}{dz} = -g \rho$$ This assumes a Cartesian coordinate system, does it not? To be more explicit, each infinitesimal volume ##dV = dx dy dz## has an equal area on the top and the bottom - whether at ##z = 0## or ##z = 100##, ##dV## is the same. But in our cylindrical coordinate system - and in our physical cylinder, a volume element ##dV = dz dθ r dr## depends on ##r##.To be even more explicit, as we integrate infinitesimal elements ##dr##, the volume is a tube of radius ##r## and thickness ##dr##, such that on the x,y (or equivalently, θ, r) plane, its area is ##A = π(r + \frac{1}{2} dr)^2 - π(r - \frac{1}{2} dr)^2## swept along the z-axis a distance ##dz##, such that $$dV = 2π r dr dz$$ - it has ##r##-dependence.

Furthermore, while in the Carteasian case, the area on the bottom of an infinitesimal cube is ##dA = dxdy##, in this cylindrical case, it's the perimeter of a circle of radius ##r + \frac{1}{2}dr## swept a distance along the z-axis ##dz##, such that ##dA = 2π(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)dz##

So I tried working it from a more basic level. I tried this process with constant ##g##, ##dV = dxdydz##, and ##dA = dxdy## and successfully re-derived the classic ##P(z) = P_0 e^{\frac{-z}{H}}## equation, so I think these steps should work for our case? At any rate, here are the steps in question:

The infinitesimal change in pressure ##dP## for an infinitesimal change in radius ##dr## should be as follows:

$$dP = \frac{dF}{dA} = \frac{dV ρ g(r)}{dA} = \frac{2π r dr dz}{2π(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)dz} ρ g(r) = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} ρ g(r)$$

Now, same as in the previous section, ##g(r) = \frac{4π^2}{T^2} r##, and using this from the wiki (which I've checked just comes straight from the ideal gas law): ##ρ = \frac{MP}{RT}##, and using my old ##H_0 = \frac{RT}{M} = g_⊕ H_⊕## (since same gas mix and temperature as Earth), so ##ρ = \frac{P}{H_0}##, so

$$dP = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} ρ g(r) = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} \frac{P}{H_0} \frac{4π^2}{T^2} r $$

Introducing another constant to clean things up a bit, a new kappa, similar to the old one in the previous section: ##\kappa = \frac{4π^2}{T^2 H_0}##,

$$dP = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} \frac{P}{H_0} \frac{4π^2}{T^2} r = \frac{r dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} P \kappa r = \kappa \frac{r^2 dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} P ⇒ \frac{dP}{\kappa P} = \frac{r^2 dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)}$$ I really don't know how I'm supposed to integrate that. So re-arranging to try to split up the fraction on the RHS so I can get all the differentials out of the denominators,

$$\frac{dP}{\kappa P} = \frac{r^2 dr}{(r + \frac{1}{2}dr)} ⇒ \frac{\kappa P}{dP} = \frac{r + \frac{1}{2}dr}{r^2 dr} = \frac{1}{rdr} + \frac{1}{2r^2}$$

$$⇒2 \kappa rdr - 2 \frac{1}{P} dP = \frac{1}{rP} dr dP$$ and I'm not even sure how to go from here with this nonlinear term. Interestingly it changes by the same form whether I choose to integrate it by ##dr## or ##dP##:

$$2 \kappa \int rdr - 2 \int \frac{1}{P} dP = \int \frac{1}{rP} dr dP$$

$$= \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P) = ln(r) \frac{1}{P} dP$$ or is it?... $$= \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P) = ln(P) \frac{1}{r} dr$$ If both are valid, then, since I don't know what else to do with equations of this form with a single differential (how am I supposed to integrate both sides if there's only something to integrate one side with respect to? An integrand without a differential is meaningless, isn't it?), I decided to try a numerical approach, so solved for the differentials: $$dP = \frac{P}{ln(r)} ( \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P))$$ $$dr = \frac{r}{ln(P)} ( \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P))$$

(eq. set 1)

Which is a bit troubling since last night I got

$$dr = \frac{r}{P} ( \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P))$$

$$dP = \frac{1}{ln(r)} ( \kappa r^2 - 2 ln(P))$$

(eq. set 2)

I really don't feel like I know what I'm doing, but I do understand many differential equations have to be solved numerically, so I took a crack at it with a little C# script. I simply start with an initial ##r## and ##P## (with all the natural logs, using units of atmospheres for ##P## didn't go well (which isn't a great sign), so I decided to try using pascals, so my initial values were ##r = 24,000 ~\rm{meters}## and ##P = 101,325 ~\rm{Pa}##.

As for the constants, recall ##\kappa = \frac{4π^2}{T^2 H_0}##, setting the rotation period ##T## such that there's earth-surface gravity on the inner surface ##g_⊕ ≈ 9.81## and the radius of the cylinder is ##R_0 = 24,000 ~\rm{meters}##, and going back to basic kinematics again, ##a = \frac{v^2}{r} = g_⊕ = \frac{v^2}{R_0}## (for artificial gravity in our co-rotating frame), and ##v = \frac{dx}{dt} = \frac{2πR_0}{T}## to get ##g_⊕ = \frac{4π^2 R_0}{T^2}##, and solving to get ##T = 2π \sqrt{\frac{R_0}{g_⊕}}##. So ##\kappa = \frac{4π^2}{T^2 H_0} = \frac{1}{\frac{R_0}{g_⊕} H_0}##, and recalling that ##H_0 = \frac{RT}{M} = g_⊕ H_⊕##, we plug that in to finally get $$\kappa = \frac{1}{R_0 H_⊕}$$

And ##H_⊕ ≈ 8,500 ~\rm{meters}##.

So, to get these curves, I had my script iterate by working off an initial ##P##, ##r## and solving eq. set 1 or 2 for ##dr## and ##dP##, then using those to advance one step, a bit like this:

C#:

//P and r and all the other constants initialized and calculated outside of the loop

for (int i = 0; i < n * 100; ++i) //n for controllable number of steps

{

PVals[i] = P; //value is stored in an array so data can be exported

rVals[i] = r;

dr = //exact form depends on which set of equations are being solved for...

dP = //exact form depends on which set of equations are being solved for...

r += dr * cf * 0.0001;

P += dP * cf * 0.0001; //cf just a scaling coefficient and the magic number is

//so I can set cf to reasonable numbers that are easier to read and still have

//the program use a large number of smaller steps

}

Results:

Altogether, though, when I ran the numerical integration, the curve I got using eq. set 2 did not look physical:

(Earth atmosphere included for reference in pink)

And using eq. set 1:

Doing some more work on eq. set 1, I've come to realize I'm pretty sure that "symmetry" I noticed actually proves that ##\frac{dP}{dr} = 1##, so it's literally just a linear slope, with perhaps a bit of a curve because of my numerical methods being very basic.

To be honest, both of those look less physical to me than the first equation, which didn't take into account the fact that there's less air resting on top of each air element due to the circumference shrinking as you approach the cylinder's z-axis:

Equation 3?:

Because, after all, while the air pressure should drop as you go towards the middle of the cylinder, it shouldn't go to zero. While modelling an atmosphere on a planet seems to work fine with modelling all the pressure as resulting from the weight of air above, with a rotating cylinder where the gravity goes to zero in a finite distance, that method seems to fail since the zero gravity at the Z-axis would imply zero weight, therefore no pressure.

But that's obviously not right, a pressurized cylinder in space won't somehow lose all its pressure just because there's no gravity.

But at the same time, eq. 0 doesn't take into account the fact that there's more than twice as much air resting on top of an element of air at ##r = 2## than at ##r = 1## since the volume increases with the square of the radius rather than linearly as it does in the base scale height model with an increase in ##z##.

On that note, that's just another power ##r## by which the curve should change. So could it be as simple as raising the exponent and then re-normalizing so that ##P(R_0) = P_0## like so?

$$P(r) = P_0 e^{\kappa (r^2 - R_0^2)}$$ $$→ P(r) = P_0 e^{\frac{\kappa}{R_0} (|r^3| - R_0^3)}$$ and let's get rid of the kappa, since it doesn't seem to be simplifying it as much as it was earlier: $$P(r) = P_0 e^{\frac{1}{2H_⊕ R_0^2} (|r^3| - R_0^3)}$$

(It may seem alarming that there's no visible dependence on the rotation rate of the cylinder, but in our derivation we defined the rotation rate such that the artificial gravity on the inner surface was the same as Earth gravity, and thus we had an extra ##g_⊕## to cancel out the##g_⊕## in ##H_0 = H_⊕ g_⊕##. So if we wanted to add that dependence back in, it would be

$$P(r) = P_0 e^{\frac{g}{2 g_{⊕} H_{⊕} R_{0}^2} (|r^3| - R_0^3)}$$

where ##g## is the spin-induced gravity on the inner surface of the cylinder, and ##g_⊕ = 9.81 ~\rm{m/s^2}## - and again, ##P_0## is the air pressure on that inner surface, ##H_⊕ ≈ 8,500~\rm{meters}## is Earth's scale height, and ##R_0## is the cylinder radius.Trying that in the numerical code, it works... disturbingly well, at least to my intuition:

That would be some great cosmic humor if it really was that simple all along...

Anyways, any help or feedback on this would be greatly appreciated. I really ought to be more familiar with working with differentials in odd problems like this.

Last edited: