etotheipi

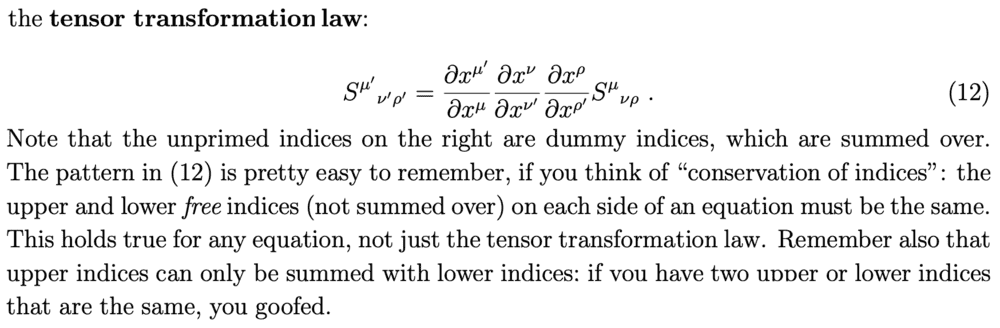

I know what Carroll refers to as 'conservation of indices' is just a trick to help you remember the pattern for transforming upper and lower components, but nonetheless I don't understand what he means in this example:

E.g. on the LHS the free index ##\nu'## is a lower index, and on the RHS, the ##\nu'## is an upper index in the denominator of a partial derivative. So maybe I'm missing the point of the heuristic...

E.g. on the LHS the free index ##\nu'## is a lower index, and on the RHS, the ##\nu'## is an upper index in the denominator of a partial derivative. So maybe I'm missing the point of the heuristic...