Camomille

- 3

- 0

Hi everyone !

I'm calling for help, for I have been unable to make sense of 1850s calculus !

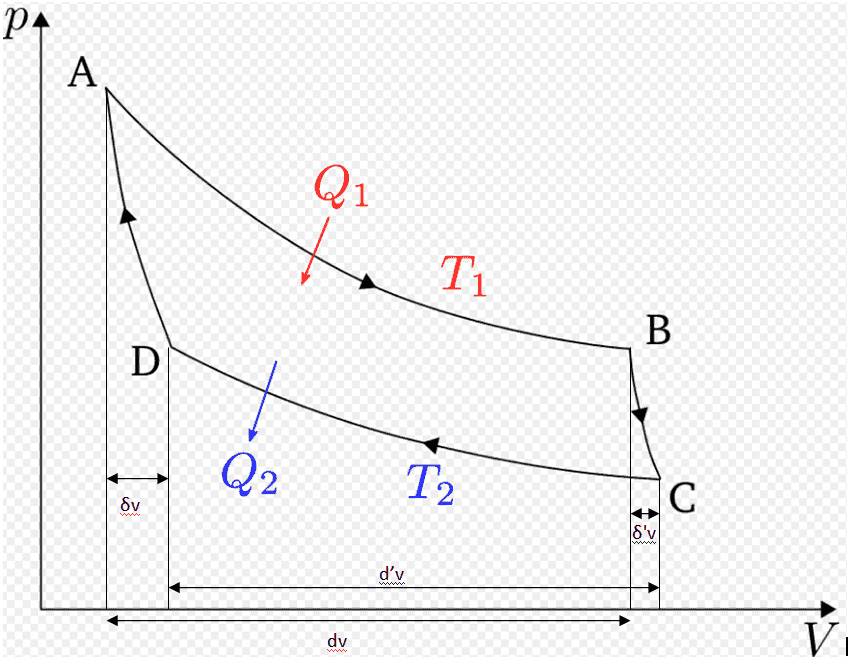

In the Mechanical Theory of Heat, R. Clausius introduces the mathematical expression of internal energy by investigating an infinitesimal Carnot cycle (that is to say all volume variations are infinitesimal) and therefore approximates every transformation as linear (cf attached graph).

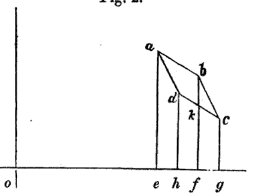

Another Carnot cycle (not infinitesimal !), with his notations.

He firstly states that Q1=

, which I can't but agree with. But he got me there :

, which I can't but agree with. But he got me there :

-Q2 =

(beware of the "-")

(beware of the "-")

Honestly, I have no clue why there should be second derivatives !

The original text for my would-be saviour : Mechanical theory of heat on Google Book

Sorry for the potential mistakes, I'm French AND a math major student !

I'm calling for help, for I have been unable to make sense of 1850s calculus !

In the Mechanical Theory of Heat, R. Clausius introduces the mathematical expression of internal energy by investigating an infinitesimal Carnot cycle (that is to say all volume variations are infinitesimal) and therefore approximates every transformation as linear (cf attached graph).

Another Carnot cycle (not infinitesimal !), with his notations.

He firstly states that Q1=

-Q2 =

Honestly, I have no clue why there should be second derivatives !

The original text for my would-be saviour : Mechanical theory of heat on Google Book

Sorry for the potential mistakes, I'm French AND a math major student !

I really hadn't understood he was trying to express what you have denoted F(v_d,t_d) in terms of F(v_a,t_a).

I really hadn't understood he was trying to express what you have denoted F(v_d,t_d) in terms of F(v_a,t_a).