Eirik

- 12

- 2

- Homework Statement

- Hi! This isn't really homework, but I'm practicing for my exam in mechanical physics and I'm really struggling with this one question!

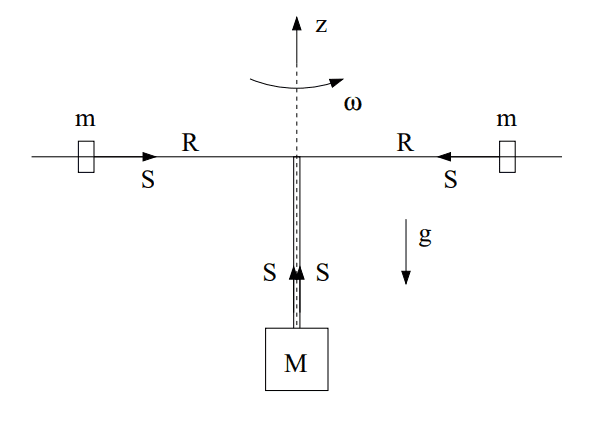

Two masses, m, are rotating around the z axis as shown in the figure on a frictionless surface, but are being pulled down by a third mass, M. Find the differential equation for the movement of the system. The masses should be considered point masses and the system initially has ##R=R_0## and ##\omega=\omega_0## It should be on the following form, where ##\alpha## and ##\beta## are constants you need to find:

- Relevant Equations

- ##\ddot R + \alpha g - \frac{\beta}{R^3}=0##, differential equation I need to find

##a_r = \ddot R -\omega^2R##, acceleration of mass m in the circle, given in task

Here's a diagram of what the system looks like:

So far I have figured out what the initial angular velocity is, if the system is balanced (no movement):

## \sum F_m = m*\frac{v^2}{R_0}-\frac{Mg}{2}=0 ##

##m \frac{v^2}{R_0}-\frac{Mg}{2}=0 ## divide both sides by m

##\omega_0 = \sqrt{\frac{Mg}{2mR_0}}##

One of the hints given for the task, was that we should consider the conservation of angular momentum:

Moment of inerty, start: ##I_0=2mR_0^2##

Angular momentum, start: ##L_0=I_0\omega_0=2mR_0^2 \sqrt{\frac{Mg}{2mR_0}} ##

I am struggling to find the equation for the angular momentum after that, however. I know that the moment of inertia should still be ##I=2mR^2##, and that ##L=I\omega##. How do I find \omega?

I also have this:

## \sum F_M = Mg-2S=M*\ddot R##

##S=m* (\ddot R -\omega^2R)## Really not sure if this one is correct

Any help would be very greatly appreciated!

So far I have figured out what the initial angular velocity is, if the system is balanced (no movement):

## \sum F_m = m*\frac{v^2}{R_0}-\frac{Mg}{2}=0 ##

##m \frac{v^2}{R_0}-\frac{Mg}{2}=0 ## divide both sides by m

##\omega_0 = \sqrt{\frac{Mg}{2mR_0}}##

One of the hints given for the task, was that we should consider the conservation of angular momentum:

Moment of inerty, start: ##I_0=2mR_0^2##

Angular momentum, start: ##L_0=I_0\omega_0=2mR_0^2 \sqrt{\frac{Mg}{2mR_0}} ##

I am struggling to find the equation for the angular momentum after that, however. I know that the moment of inertia should still be ##I=2mR^2##, and that ##L=I\omega##. How do I find \omega?

I also have this:

## \sum F_M = Mg-2S=M*\ddot R##

##S=m* (\ddot R -\omega^2R)## Really not sure if this one is correct

Any help would be very greatly appreciated!