Discussion Overview

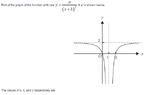

The discussion revolves around understanding horizontal asymptotes in the context of rational functions, particularly focusing on the role of constants in the function's behavior as the variable approaches infinity. Participants explore the implications of the denominator increasing and how it affects the overall value of the function.

Discussion Character

- Exploratory

- Technical explanation

- Debate/contested

- Mathematical reasoning

Main Points Raised

- Some participants express confusion about why the constant +c represents the horizontal asymptote, questioning the relationship between the denominator and the asymptotic behavior.

- One participant suggests that as the denominator increases without bound, the fraction approaches zero, leading to the conclusion that the horizontal asymptote is y=c.

- Another participant provides specific numerical examples to illustrate how the function behaves for large values of x, showing that the output approaches c.

- There is a discussion about the conditions under which limits apply, with references to the properties of limits and their implications for the asymptotic behavior of the function.

- Some participants attempt to clarify their understanding by working through specific examples, but there is uncertainty about the calculations and the implications of the results.

- A later reply revisits the initial question, emphasizing the need to consider large values of x to understand the asymptotic behavior better.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants do not reach a consensus on the explanation of horizontal asymptotes, with some expressing confusion and others providing differing perspectives on the calculations and reasoning involved.

Contextual Notes

There are limitations in the discussion regarding the assumptions made about the behavior of the function as x approaches infinity, and some participants appear to struggle with the mathematical steps involved in their reasoning.

Who May Find This Useful

This discussion may be useful for students and individuals seeking to understand the concept of horizontal asymptotes in rational functions, particularly those grappling with the mathematical reasoning behind limits and asymptotic behavior.