Ookke

- 172

- 0

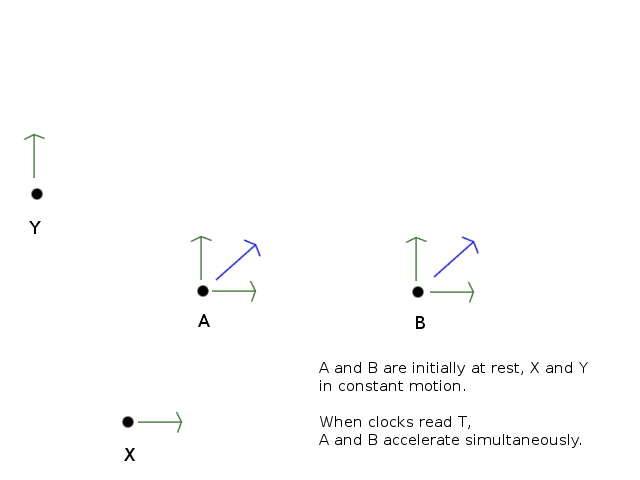

Please see the pictures. In lab frame, we have rockets A and B initially at rest and clocks in sync. When clocks reach certain time T, both A and B accelerate at 45 degrees to up-right direction. There are inertial observers X and Y, which match the velocity x- and y-components that the rockets are going to have.

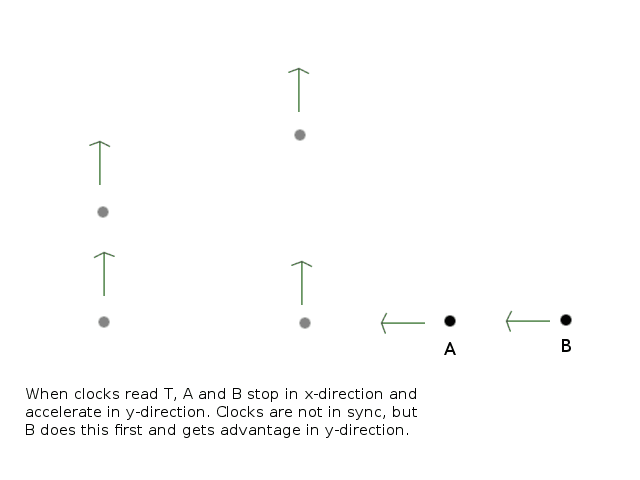

In X's frame, the rockets are initally moving left with some length contraction, but the clocks are not in sync. B's clock is ahead, so B reaches time T first, when it stops in x-direction and accelerates in y-direction. Soon after, A reaches T also and does the same, but B has gained advantage in y-direction that seems permanent.

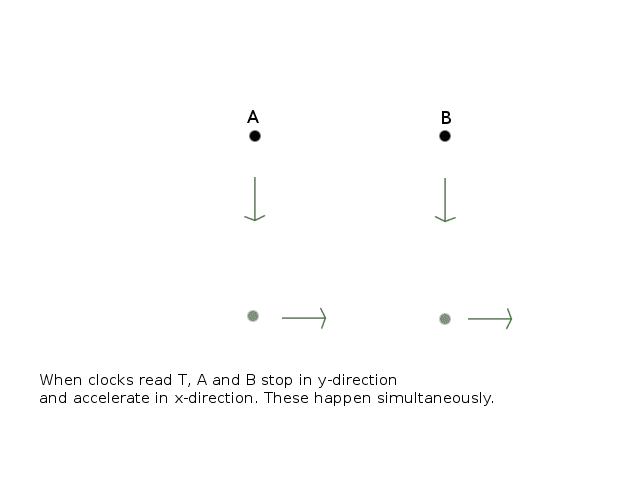

In Y's frame, the rockets are initially moving down and the clocks are in sync. Both reach T simultaneously, stop in y-direction and accelerate in x-direction. After stopping in y-direction, the setup is practically identical with Bells's spaceship paradox (without a rope, though). A and B do not have distance in y-direction in this frame.

After the accelerations are done, A and B will end up into their final common rest frame. Strangely enough, things in this frame seem quite different depending on our point of view. If we start from X's frame and jump into final rest frame, we can expect that A and B do have some distance in y-direction. But if we start from Y's frame and jump into final rest frame, we can expect to have somewhat increased distance in x-direction (like Bell's) but no distance in y-direction. This doesn't seem right. Things should not be that relative.

In X's frame, the rockets are initally moving left with some length contraction, but the clocks are not in sync. B's clock is ahead, so B reaches time T first, when it stops in x-direction and accelerates in y-direction. Soon after, A reaches T also and does the same, but B has gained advantage in y-direction that seems permanent.

In Y's frame, the rockets are initially moving down and the clocks are in sync. Both reach T simultaneously, stop in y-direction and accelerate in x-direction. After stopping in y-direction, the setup is practically identical with Bells's spaceship paradox (without a rope, though). A and B do not have distance in y-direction in this frame.

After the accelerations are done, A and B will end up into their final common rest frame. Strangely enough, things in this frame seem quite different depending on our point of view. If we start from X's frame and jump into final rest frame, we can expect that A and B do have some distance in y-direction. But if we start from Y's frame and jump into final rest frame, we can expect to have somewhat increased distance in x-direction (like Bell's) but no distance in y-direction. This doesn't seem right. Things should not be that relative.