Math Amateur

Gold Member

MHB

- 3,920

- 48

I am reading the book "Several Real Variables" by Shmuel Kantorovitz ... ...

I am currently focused on Chapter 2: Derivation ... ...

I need help with an aspect of Kantorovitz's Example 4 on page 66 ...

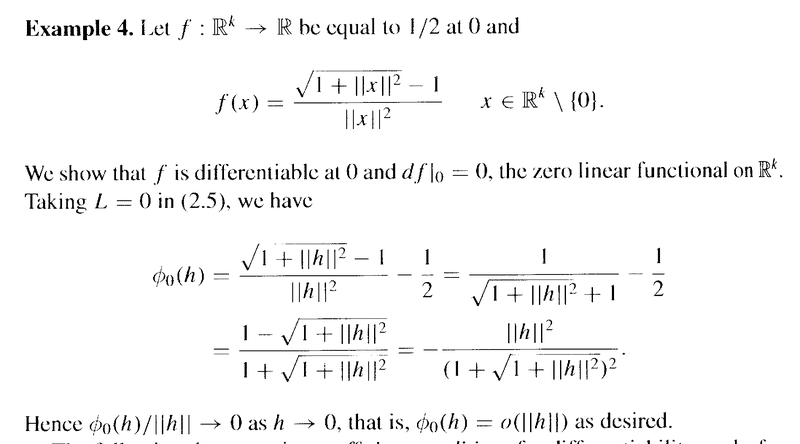

Kantorovitz's Example 4 on page 66 reads as follows:

In the above example, Kantorovitz shows that##\phi_0 (h) = - \frac{ \| h \|^2 }{( 1 + \sqrt{ 1 + \| h \|^2 )}^2 }##Kantorovitz then declares that ## \frac{ \phi_0 (h) }{ \| h \| } \rightarrow 0## as ##h \rightarrow 0## ... ...Can someone please show me how to demonstrate rigorously that this is true ... that is that

## \frac{ \phi_0 (h) }{ \| h \| } \rightarrow 0## as ##h \rightarrow 0## ... ...

Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter============================================================================================

***NOTE***

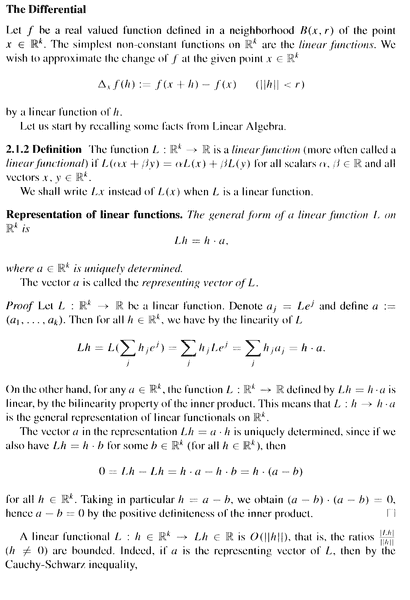

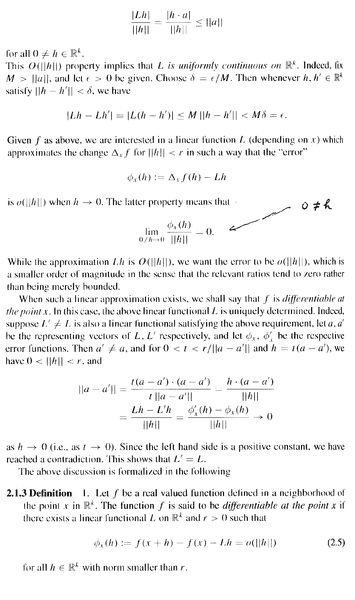

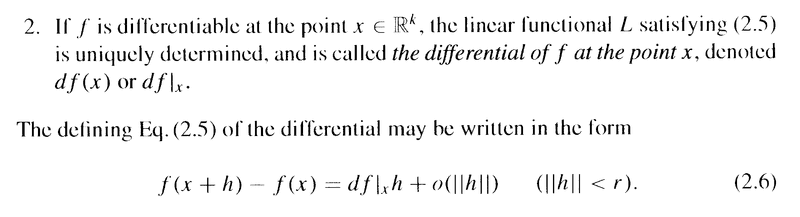

Readers of the above post may be helped by having access to Kantorovitz' Section on "The Differential" ... so I am providing the same ... as follows:

Hope that helps readers understand the context and notation of the above post ,,, ,,,

Hope that helps readers understand the context and notation of the above post ,,, ,,,

Peter

I am currently focused on Chapter 2: Derivation ... ...

I need help with an aspect of Kantorovitz's Example 4 on page 66 ...

Kantorovitz's Example 4 on page 66 reads as follows:

In the above example, Kantorovitz shows that##\phi_0 (h) = - \frac{ \| h \|^2 }{( 1 + \sqrt{ 1 + \| h \|^2 )}^2 }##Kantorovitz then declares that ## \frac{ \phi_0 (h) }{ \| h \| } \rightarrow 0## as ##h \rightarrow 0## ... ...Can someone please show me how to demonstrate rigorously that this is true ... that is that

## \frac{ \phi_0 (h) }{ \| h \| } \rightarrow 0## as ##h \rightarrow 0## ... ...

Help will be much appreciated ...

Peter============================================================================================

***NOTE***

Readers of the above post may be helped by having access to Kantorovitz' Section on "The Differential" ... so I am providing the same ... as follows:

Peter

Attachments

-

Kantorovitz - Example 4 ... Page 66 ... ... .png18.8 KB · Views: 954

Kantorovitz - Example 4 ... Page 66 ... ... .png18.8 KB · Views: 954 -

Kantorovitz - 1 - Sectiion on the DIfferential ... PART 1 ... .png27.4 KB · Views: 531

Kantorovitz - 1 - Sectiion on the DIfferential ... PART 1 ... .png27.4 KB · Views: 531 -

Kantorovitz - 2 - Sectiion on the DIfferential ... PART 2 ... .png34.9 KB · Views: 512

Kantorovitz - 2 - Sectiion on the DIfferential ... PART 2 ... .png34.9 KB · Views: 512 -

Kantorovitz - 3 - Sectiion on the DIfferential ... PART 3 ... .png13.2 KB · Views: 521

Kantorovitz - 3 - Sectiion on the DIfferential ... PART 3 ... .png13.2 KB · Views: 521

Last edited: