Discussion Overview

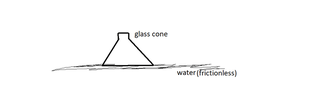

The discussion revolves around whether a body behaves as a point mass when at rest, specifically when no external force is applied. Participants explore the implications of this behavior in the context of Newton's laws and the motion of the center of mass, considering both translational and rotational dynamics.

Discussion Character

- Exploratory

- Technical explanation

- Debate/contested

- Mathematical reasoning

Main Points Raised

- Some participants assert that a body behaves as a point mass when a force is applied, questioning if this holds true when no external force is present.

- Others argue that a rigid body does not behave as a point mass due to potential rotational motion, even if the center of mass moves as if all mass is concentrated there.

- It is proposed that when external forces sum to zero, the center of mass will remain at rest or move at constant speed, suggesting that the mass can be treated as concentrated at the center of mass for problem-solving purposes.

- Some participants emphasize the importance of considering both translational and rotational motion, noting that external forces can lead to changes in rotational kinetic energy.

- There are discussions about the complexities involved in conservation laws when both translational and rotational motions are present.

- One participant mentions that the concept of treating a body as a point mass depends on the size of the body relative to other distances involved in the problem.

Areas of Agreement / Disagreement

Participants express differing views on whether a body can be treated as a point mass at rest without external forces. While some agree on the conditions under which this is valid, others highlight the complications introduced by rotational motion and the need for careful consideration of forces and torques.

Contextual Notes

Limitations include the dependence on definitions of point mass and center of mass, as well as the unresolved implications of rotational motion on translational dynamics. The discussion does not reach a consensus on the treatment of bodies at rest as point masses.