member 731016

- Homework Statement

- Please see below

- Relevant Equations

- Please see below

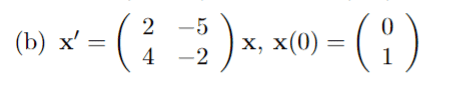

For this problem,

I am trying to find the fundamental matrix, however, the eigenvalues are both imaginary and so are the eigenvectors. That is, ##\lambda_1 = 4i, \lambda_2 = -4i##

##v_1 = (1 + 2i, 2)^T##

##v_2 = (1 - 2i, 2)^T##

So I think I just have an imaginary matrix? This is because the general solution is ##\vec x = c_1(1 + 2i, 2)^T e^{4it} + c_2(1 - 2i, 2)^T e^{-4it}##, then does someone please know whether I can just write the system in the form ##\vec x = \vec Φ \vec c## where ##c = (c_1, c_2)^T## and Φ is complex?

Thanks!

I am trying to find the fundamental matrix, however, the eigenvalues are both imaginary and so are the eigenvectors. That is, ##\lambda_1 = 4i, \lambda_2 = -4i##

##v_1 = (1 + 2i, 2)^T##

##v_2 = (1 - 2i, 2)^T##

So I think I just have an imaginary matrix? This is because the general solution is ##\vec x = c_1(1 + 2i, 2)^T e^{4it} + c_2(1 - 2i, 2)^T e^{-4it}##, then does someone please know whether I can just write the system in the form ##\vec x = \vec Φ \vec c## where ##c = (c_1, c_2)^T## and Φ is complex?

Thanks!