- 1,047

- 795

The Wikipedia page on the Hall effect says:

I probably don't have the math ability or the time to master solid state physics in all its glory, but I am hoping to get to a heuristic picture of the P-type Hall effect that, at the very least, won't be "not even wrong". My attempt is as follows.

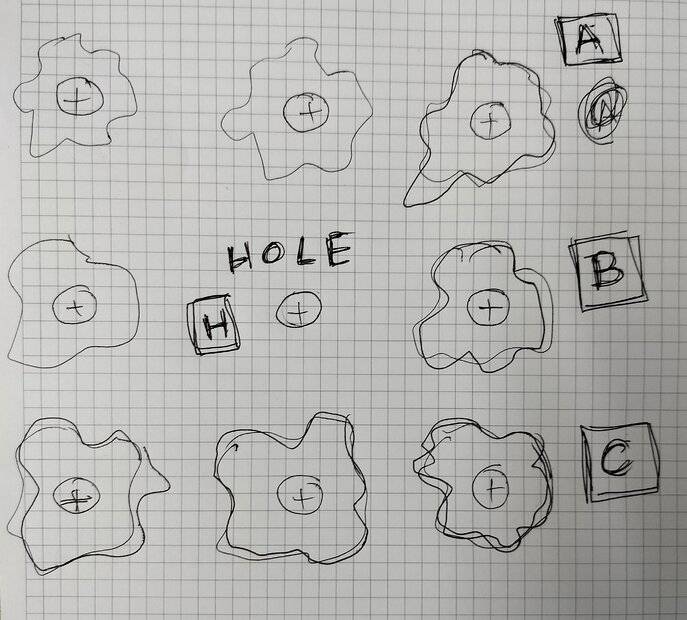

The sketch shows 9 atoms in a crystal. The amoeba-like wiggly shapes represent wavefunctions of bound(?) electrons that can potentially decay(?) or tunnel(?) into the central position, which is currently short of one electron. In the absence of an electric field, such events will be very rare at room temperature.

But now let's apply an electric field such that the system needs a net movement of electrons towards the left. The wavefunctions around A, B and C are the ones now likely to jump to the central position, with B perhaps being slightly more favored than A or C; but A and C will be equal to each other in their probability of ending up around H.

Also, since there is a charge deficit around H, the initial wavefunctions A, B and C should have a slight bias with higher amplitude concentrated in the region towards H than on the opposite side. This would also affect the spatial momentum profile.

Now let us add a magnetic field such that holes are now induced to drift upwards. To make this true, it has to be the case that the magnetic field distorts the wavefunctions such that P(A) > P(B) > P(C) are now the new probabilities for jumping to the central position.

So... is the above picture reasonably OK, or is it wrong, or "not even wrong"? If it is generally on the right track, how can one flesh it out to explain how P(A) > P(B) > P(C)? Maybe we have to consider various possible initial orientations of spin and orbital momenta with respect to the magnetic field axis and sum / average over them? Or what?

A common source of confusion with the Hall effect in such (P-type) materials is that holes moving one way are really electrons moving the opposite way, so one expects the Hall voltage polarity to be the same as if electrons were the charge carriers as in most metals and n-type semiconductors. Yet we observe the opposite polarity of Hall voltage, indicating positive charge carriers. Of course there are no actual positrons or other positive elementary particles carrying the charge in p-type semiconductors, hence the name "holes". This apparent contradiction can only be resolved by the modern quantum mechanical theory of quasiparticles wherein the collective quantized motion of multiple particles can, in a real physical sense, be considered to be a particle in its own right (albeit not an elementary one).

I probably don't have the math ability or the time to master solid state physics in all its glory, but I am hoping to get to a heuristic picture of the P-type Hall effect that, at the very least, won't be "not even wrong". My attempt is as follows.

The sketch shows 9 atoms in a crystal. The amoeba-like wiggly shapes represent wavefunctions of bound(?) electrons that can potentially decay(?) or tunnel(?) into the central position, which is currently short of one electron. In the absence of an electric field, such events will be very rare at room temperature.

But now let's apply an electric field such that the system needs a net movement of electrons towards the left. The wavefunctions around A, B and C are the ones now likely to jump to the central position, with B perhaps being slightly more favored than A or C; but A and C will be equal to each other in their probability of ending up around H.

Also, since there is a charge deficit around H, the initial wavefunctions A, B and C should have a slight bias with higher amplitude concentrated in the region towards H than on the opposite side. This would also affect the spatial momentum profile.

Now let us add a magnetic field such that holes are now induced to drift upwards. To make this true, it has to be the case that the magnetic field distorts the wavefunctions such that P(A) > P(B) > P(C) are now the new probabilities for jumping to the central position.

So... is the above picture reasonably OK, or is it wrong, or "not even wrong"? If it is generally on the right track, how can one flesh it out to explain how P(A) > P(B) > P(C)? Maybe we have to consider various possible initial orientations of spin and orbital momenta with respect to the magnetic field axis and sum / average over them? Or what?

Last edited: