Aafia

- 70

- 1

I wonder how were historically functions of the body organs determined? I mean how they dermined working of circulatory system , Nervous system, Excretory system etc?

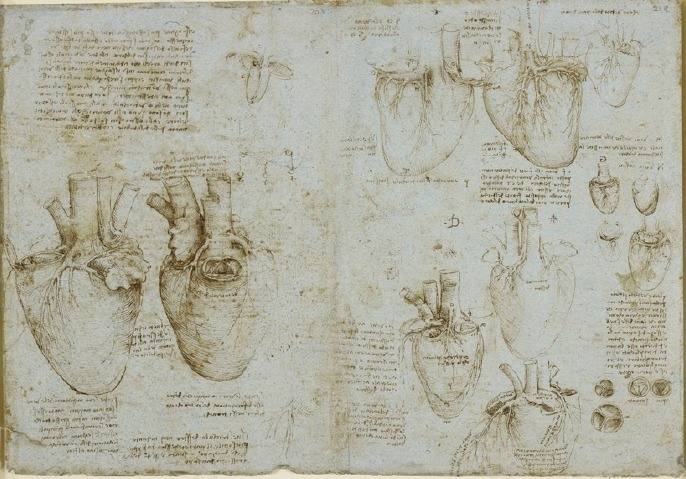

The functioning of body organs has historically been determined through observation of injuries, tracking blood flow, and studying chemical reactions. Early understandings were often influenced by superstition and lacked scientific rigor, but advancements in anatomy and physiology have led to a more precise knowledge base. Key figures like Leonardo da Vinci contributed to early concepts of blood circulation, paving the way for modern discoveries. Current methodologies include dissection, temporary inactivation of proteins, and in vitro testing to explore organ functions and their interdependencies.

PREREQUISITESStudents in biology and medicine, researchers in anatomy and physiology, and professionals involved in medical education and experimentation will benefit from this discussion.

May you achieve everything you desire. :) BTW Is it right that A very common way of getting information on the function of an organ, part of an organ (such as a region of the brain) or a protein is to look at the outcome (symptoms or phenotype) in cases where it is not functional?Fervent Freyja said:Historically, body function had been very difficult to determine, much of it had been bad guesswork and there were many superstitions surrounding the body. After we began studying anatomy more thoroughly, the body of knowledge grew enough to ignite many the observations and experiments that result in what we know today. Thanks to contribution by hundreds of thousands of people.

Oftentimes, the functions in the body we now know of began as simple ideas. For example, Leonardo da Vinci had came close to the idea that blood circulated in the body in the 1500s through his dissection of cadavers; although, someone else made the official discovery a century later.

Much of what appears to be common sense or intuitive about our body or nature actually isn't. Sometimes, we make a huge leap in understanding, but anatomy and physiology is primarily built upon by many people working together over the years. As it stands, there is still much left to discover about the functions in the body- plenty to keep people busy for centuries!

I'm hoping to be able to participate in or at least observe a human dissection this semester (one of my prior Professors is doing some work in mapping lymphatic vessels)!