mathmari

Gold Member

MHB

- 4,984

- 7

Hey!

Let $K$ be a circle with center $M=(x_0 \mid y_0)$ and radius $r$ and let $P_1=(x_1\mid y_1)$ be a point of the circle.

I have done the following tofind the equation of the tangent that passes through $P_1$:

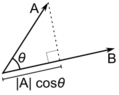

The tangent passes through $P_1$ and is perpendicular to $MP$, then let $m_T$ be the slope of the tangent and $m_{MP}$ be the slope of $MP$, then it holds that $m_T\cdot m_{MP}=-1$.

The equation of the tangent is in the form $y=m_Tx+n$.

The slope of $MP$ is $\frac{y_1-y_0}{x_1-x_0}$. The slope of the tangent is therefore \begin{equation*}m_T=-\frac{1}{m_{MP}}=-\frac{1}{\frac{y_1-y_0}{x_1-x_0}}=-\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}\end{equation*}

We get that \begin{equation*}y=-\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x+n\end{equation*}

Since the tangent passes through $P_1=(x_1\mid y_1)$, it satisfies the equation of the tangent, so we have the following: \begin{equation*}y_1=-\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x_1+n \Rightarrow n=y_1+\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x_1\end{equation*}

The equation of the tangent is therefore \begin{align*}&y=-\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x+y_1+\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x_1 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)x+y_1(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)x_1 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)x+y_1(y_1-y_0)-y_0(y_1-y_0)+y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)x_1-(x_1-x_0)x_0+(x_1-x_0)x_0 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)x+(y_1-y_0)(y_1-y_0)+y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)(x_1-x_0)+(x_1-x_0)x_0 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)x+(y_1-y_0)^2+y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)^2+(x_1-x_0)x_0 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)(x-x_0)+(y_1-y_0)^2+y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)^2 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y-y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)(x-x_0)=(y_1-y_0)^2+(x_1-x_0)^2 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)(y-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)(x-x_0)=(y_1-y_0)^2+(x_1-x_0)^2\end{align*}

The equation of the circle is $(x-x_0)^2+(y-y_0)^2=r^2$. Since $P_1$ is a point of the circle we have that $(x_1-x_0)^2+(y_1-y_0)^2=r^2$.

So we get the following equation of the tangent: \begin{equation*}(y_1-y_0)(y-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)(x-x_0)=r^2\end{equation*}

Is everything correct? (Wondering) Let $K$ be a circle with center $M(x_0\mid y_0)$ and radius $r$. For each point $P$ outside the circle, let $g_P$ be the line through the two intersection points of the tangent to $K$ by $O$.

What do we do in this case where $P$ is outside the circle to determine the equation of the tangent? Could you give me a hint?

Let $K$ be a circle with center $M=(x_0 \mid y_0)$ and radius $r$ and let $P_1=(x_1\mid y_1)$ be a point of the circle.

I have done the following tofind the equation of the tangent that passes through $P_1$:

The tangent passes through $P_1$ and is perpendicular to $MP$, then let $m_T$ be the slope of the tangent and $m_{MP}$ be the slope of $MP$, then it holds that $m_T\cdot m_{MP}=-1$.

The equation of the tangent is in the form $y=m_Tx+n$.

The slope of $MP$ is $\frac{y_1-y_0}{x_1-x_0}$. The slope of the tangent is therefore \begin{equation*}m_T=-\frac{1}{m_{MP}}=-\frac{1}{\frac{y_1-y_0}{x_1-x_0}}=-\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}\end{equation*}

We get that \begin{equation*}y=-\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x+n\end{equation*}

Since the tangent passes through $P_1=(x_1\mid y_1)$, it satisfies the equation of the tangent, so we have the following: \begin{equation*}y_1=-\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x_1+n \Rightarrow n=y_1+\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x_1\end{equation*}

The equation of the tangent is therefore \begin{align*}&y=-\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x+y_1+\frac{x_1-x_0}{y_1-y_0}x_1 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)x+y_1(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)x_1 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)x+y_1(y_1-y_0)-y_0(y_1-y_0)+y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)x_1-(x_1-x_0)x_0+(x_1-x_0)x_0 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)x+(y_1-y_0)(y_1-y_0)+y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)(x_1-x_0)+(x_1-x_0)x_0 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)x+(y_1-y_0)^2+y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)^2+(x_1-x_0)x_0 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y=-(x_1-x_0)(x-x_0)+(y_1-y_0)^2+y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)^2 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)y-y_0(y_1-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)(x-x_0)=(y_1-y_0)^2+(x_1-x_0)^2 \\ & \Rightarrow (y_1-y_0)(y-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)(x-x_0)=(y_1-y_0)^2+(x_1-x_0)^2\end{align*}

The equation of the circle is $(x-x_0)^2+(y-y_0)^2=r^2$. Since $P_1$ is a point of the circle we have that $(x_1-x_0)^2+(y_1-y_0)^2=r^2$.

So we get the following equation of the tangent: \begin{equation*}(y_1-y_0)(y-y_0)+(x_1-x_0)(x-x_0)=r^2\end{equation*}

Is everything correct? (Wondering) Let $K$ be a circle with center $M(x_0\mid y_0)$ and radius $r$. For each point $P$ outside the circle, let $g_P$ be the line through the two intersection points of the tangent to $K$ by $O$.

What do we do in this case where $P$ is outside the circle to determine the equation of the tangent? Could you give me a hint?